The Covid-19 pandemic disrupted movement between Hong Kong and Macau on a scale unseen since the weeks immediately after the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in late 1941. During the war years, one of the institutions that enabled communications between the two neighbouring territories was the Macau Delegation of the Portuguese Red Cross Society, forerunner of today’s Macau Red Cross (澳門紅十字會). Our colleague Dr Helena F. S. Lopes has written about this in the latest blog post on the website of Project Macau History, created and directed by Hong Kong History Project project alumna Dr Catherine S. Chan.

Category: Uncategorized

Guest blog: Reynold Tsang, “Comment, Like, and Share!” – The Boom of Hong Kong’s History Pages. Part 2: Challenges and Opportunities

“Comment, Like, and Share!” – The Boom of Hong Kong’s History Pages

(Part 2: Challenges and Opportunities)

by

Reynold Tsang

(DPhil student, University of Oxford)

In mid-March 2021, a small “scandal” erupted in the public history circle of Hong Kong. Earlier that month, a new “Hong Kong history” page is established. The admin of that new history page is an employee of a pro-government research centre, which happens to run an apparent “blue” (pro-government) history page. The identity of this admin was soon discovered by some “yellow” (pro-democracy) history pages. These “yellow pages” are highly suspicious of the admin’s motive and warned their readers about that. They worry that the new history page would disguise as a “neutral” page and carry out missions assigned by the pro-government research centre, such as instilling the official historical narrative and framing public opinions in favour of the government. After the exposure, the admin of the new history page did not deny nor admit their pro-government stance. In response to suspicion, their criticised the “yellow pages” for making baseless accusations and judging the page for its political stance instead of contents. The second point is indeed worth considering, should we judge a history page based on its objectives and ideology? Nevertheless, one “yellow page” also makes a good point – public historians should defend the genuineness of history and, more importantly, uphold the values and morals of society. This humanistic approach coincides with the proposition of some liberal historians that historians should assist the pursuit of social justice and call out oppression.

The above incident reflects the complication of running history pages in Hong Kong. If you have no idea what a history page is, please check out Part 1 of this blogpost and the “History Pages, Channels, and Websites in Hong Kong” list. In Part 2, I will share my observations and thoughts on the present situation and future of history pages. My discussion will focus on the “Hong Kong history” pages.

Challenges

Politics first! I guess this is more a concern than a challenge. As shown above, history pages could not escape from the political polarisation of Hong Kong society. But like I mentioned in Part 1, it is natural for historians (professional or amateur) to present their opinions and make arguments. However, some history pages went to the extreme and asserted very biased viewpoints to support their political stance. For example, a “blue page” recently provided an “alternative perspective” on the June Fourth Incident. It claimed that the Tiananmen protesters burnt down “few hundreds” of armoured cars and snatched some of them to attack the army, killing a lot of soldiers. Meanwhile, it mentioned nothing about the army crackdown on protestors. What the page claimed might be true to some extent, discounting the exaggeration, but it deliberately ignored all evidence against its standpoint and completely failed to present the general situation (not to mention the full one). On the other hand, a few “yellow pages” occasionally romanticised British colonial rule over Hong Kong in the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries, when racial discrimination and corruption were grave. Nonetheless, I think it is pointless for history pages to completely ignore politics and even ban political comments (as suggested by some “apolitical” readers) because history and politics are inseparable. But history pages should refrain from becoming political commentators.

Back to the question of whether we should judge a history page based on its political stance. I think it is not fair to denounce a history page if its contents are accurate and reasonable. But readers should always bear in mind the political stance and background of a history page, as they inevitably affect the page’s narrative, such as the choice of topics and use of words. Anyway, I appreciate history pages embracing a humanistic spirit.

Money, Money, Money. Funding is a major problem for both historians and history pages. Except those with affiliation, most history pages are self-funded, and most admins cannot afford to run their pages full-time. In theory, operating a history page does not involve much expense, but those willing and able to pay will have an advantage. In fact, there is a financial imbalance between the so-called “blue pages” and other pages. The former are well funded by their parent organisations. Most of them employ a team of full-time admins and editors to manage their pages and place advertisements on social media (aka buying reach rates). Their financial strength explains why some “yellow pages” are so anxious about the expansion of “blue pages”, as it would not be a fair competition. In the meantime, some self-funded history pages explore new funding options, such as crowdfunding and membership subscription. For example, more and more pages turn to Patreon (a membership platform) these days. However, making some contents exclusive to paid members might deter new followers and curtail their reach on social media.

The new situation under the National Security Law. I think this point does not need much explanation. Some history pages probably have a hard time navigating in the new situation. Furthermore, self-censorship will likely be more pervasive. Anyway, this new situation may also be an opportunity for some history pages.

Quality control. Unlike academic publications, there is no peer review for history posts on social media. In addition, some admins and editors of history pages are not history graduates and receive no training in writing history.[1] So, the quality of history pages varies considerably, with some reaching the level of academic studies and some getting basic historical facts wrong. In order to react quickly to hot topics on the internet, some history pages (especially the KOLs) would sacrifice quality for speed and deliver somewhat hollow or inaccurate contents.[2] I hope history pages can crosscheck their information even when posting in haste.

Staying active! Although the number of history pages increased significantly in the past few years, not every page survives. Some notable defunct pages include Decoding Hong Kong’s History (by Liber Research Community and Demosisto), Hong Kong Chronicle, Cemetery Study, and Hong Kong’s First (English website and discussion forum). These pages stopped operating for different reasons, such as the death or departure of the chief admin and the disbandment of the parent organization. Constantly updating and coming up with new contents is undoubtedly hard work, especially pages managed by one or two people.

Opportunities

Bridging academia and the public. The latest academic studies and findings, especially for humanities subjects, often take ages to reach the public. Sometimes I encounter the awkward situation of people asking me why no one studies a certain historical topic, even if that topic is quite well-researched. I see the potential of history pages in narrowing the gap between academia and the public (at least the netizens). In fact, a few history pages are already doing that, such as the Hong Kong History Project. It has done an excellent job in introducing young historians and history postgraduates on Hong Kong history and their current research. I look forward to seeing more history pages introducing, summarising, and explaining the latest research projects and academic studies.

Advanced research. Apart from sharing and condensing academic studies, some history pages are capable of conducting advanced research of their own. As mentioned earlier, a few history pages can produce contents comparable to academic studies. Their use of sources astonished me particularly. Other than basic primary sources like photos and newspapers, they also reference various archival materials, such as correspondence, minutes, maps, and statistics. Some even provide a bibliography at the end of their posts. I would encourage history pages to conduct more advanced research, as I see the demand for more in-depth contents among readers. Anyway, it is not a “must”. Many readers (including me) still enjoy reading historical anecdotes and trivia.

Power in unity. In the previous year, there are more and more exchanges and collaboration between different history pages, ranging from sharing each other’s posts to doing a live discussion together. The power of history pages united is best reflected in the campaign to stop the demolishment of Ex-Sham Shui Po Service Reservoir in late December 2020. Hong Kong Heritage Exploration was the first to post about the demolishment of the underground reservoir. Its post and photos soon spread like wildfire on the internet, thanks to the “sharing” of multiple history pages and their followers. Later that day, around twenty history pages signed a joint statement to petition for the conservation of the underground reservoir. The united effort of history pages (including different research on the history of the reservoir), coupled with the help of various public figures and individuals, successfully forced the government to stop the demolishment and conserve the reservoir instead. We should not underestimate the influence of history pages working together. I hope there will be more cooperation and crossover between pages. Perhaps an alliance? Or a discussion forum (there are several Hong Kong history forums for Chinese readers on Facebook, but their discussion quality and standing could not compare with their English counterparts)?

The above are just my personal opinions. Please do not see them as guidelines or criticism. I hope history pages with different political stance and from different background can thrive together, as there shouldn’t be just one single “correct” narrative. Some can argue there was more good than harm and some can argue there was more harm than good, as long as the argument is supported by evidence. Last but not least, I would like to thank all history pages for promoting history, especially Hong Kong history, and making history fun.

[1] Please note that a history degree does not guarantee good history posts and a person with no history background does not necessarily produce bad history posts.

[2] I did not count Key Opinion Leaders (KOLs) as pages in this blogpost, but many KOLs in politics would talk about history, and a few of them would discuss history regularly.

Guest blog: Reynold Tsang, ‘“Comment, Like, and Share!” – The Boom of Hong Kong’s History Pages’

HKHP: In the past decade or so, Hong Kong witnessed a blossoming of social media pages on Hong Kong history (blogs, Facebook pages, Twitter accounts, Patreon pages – you name it). They provide much great content and help make Hong Kong history more accessible to the general public. In April this year, we participated in a panel discussion on ‘the Future of “Hong Kong History” as a public history and discipline’. Chair of the panel Reynold Tsang, now DPhil student at the University of Oxford, asked enlightening questions about what academia and public history pages could learn from each other. We thought this was a question worth further exploring, and Reynold has kindly agreed to contribute a series of two blogposts to give us an overview of these public history pages, and to share with us some observations that he, an academic historian, has made about such pages.

Before we hand over to Reynold, we wanted to note that Reynold has recently compiled a list, “History Pages, Channels and Websites in Hong Kong”, to record the blossoming of history pages in the past decade or so. The list has 88 entries in total, in which 13 offer English content. Most of them focus on Hong Kong history. Readers of this blogpost might find it useful to also check out this list as they read this blogpost.

“Comment, Like, and Share!” – The Boom of Hong Kong’s History Pages

(Part 1: Overview)

by

Reynold Tsang

(DPhil student, University of Oxford)

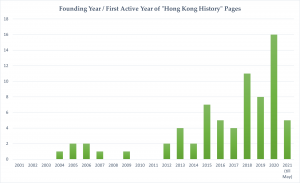

On 18th October 2020, nearly 10,000 people flocked to the Hong Kong Museum of History to visit the “Hong Kong Story” exhibition for one last time, as this flagship exhibition for nineteen years would be closed for a major revamp. Some visitors took photos of every object, text panel, and decoration in the exhibition as if the city’s history would be lost forever after the revamp. Hongkongers’ interest in history is not an ephemeral trend triggered by the closure of a twenty-year-old exhibition. In recent years, the subject of history, especially Hong Kong history, has gained enormous public interest. Many young history enthusiasts set up social media pages, channels, and websites (pages in short) to discuss and promote history. In 2020 alone, at least sixteen history pages were established.

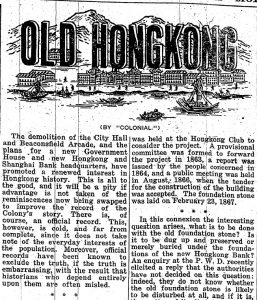

Public history essays and podcasts are not something new in Hong Kong. They first appear as historical anecdotes in newspapers and on the radio. Early examples include the “Old Hongkong” column by Colonial (Vincent Jarrett) on South China Morning Post in the 1930s, the “香港史地” column by Ye Lingfeng (葉靈鳳) on Sing Tao Daily and the “香港掌故錄” programme on RTHK in the mid-twentieth century. Their contents are surprisingly similar to contemporary history pages. Some recurrent topics include the etymology of “Hong Kong”, the past and present of streets and buildings, changes on the coastline, and pirates.

In Part 1 of this two-part blogpost, I will provide an overview on the blossoming of history pages in the past few years. My discussion will focus on the “Hong Kong history” pages.

When did history pages appear? The first batch of history pages emerged shortly after the prevalence of Facebook in the late 2000s. Research groups such as 香港歷史研究社, Conservancy Association Centre for Heritage, and Society of Hong Kong History opened their Facebook pages in the early 2010s. At that time, these pages mainly served as a media platform for their organisations, publicizing their latest publications and events. Meanwhile, English-language pages developed a bit differently. Founded in 2009 and 2012 respectively, Gwulo and the Industrial History of Hong Kong Group started out as websites and welcome contributions from the public. They have now become prominent “Hong Kong history” discussion forums for English readers.

When did the boom take place and why? The number of history pages, particularly those in Chinese, increased significantly since the mid-2010s. Unlike their predecessors, the new batch of history pages usually centred on social media without a parent organisation. Since every page has its own objective and vision, it is hard to generalise the reason for the boom. However, many pages share the aim to “preserve” and “pass down” Hong Kong history, with some warning the city’s past is in danger of being forgotten. Apart from fearing the loss of Hong Kong history, there is a general concern about the official interpretation or reshaping of Hong Kong history. This explains why people rushed to the “Hong Kong Story” exhibition before it is “reinterpreted” and recorded everything in it. The Umbrella Movement in 2014 and the subsequent political environment no doubt contributed to this worry. Fearing increasing government control over history education, some history enthusiasts present their own version of Hong Kong history on social media to counter the official historical narrative.[1] The 2019-2020 Hong Kong Protests and the 2020 HKDSE History Exam Controversy likely intensified the boom. Between January 2019 and May 2021, nearly 30 “Hong Kong history” pages were established.

The next question comes naturally. “Is this a ‘yellow’ (pro-democracy) page or a ‘blue’ (pro-government) page?” This is a question typical to Hong Kong’s polarised society, but it is in no way senseless. “All history is contemporary history.”[3] History can hardly be neutral, and historians are meant to make arguments. As touched on above, some history pages aim to debunk the official historical narrative and present history from a Hongkonger (instead of Chinese or colonial) perspective. These so-called “yellow pages” often debate (indirectly) with the government and the pro-government camp on controversial historical topics, for example, “When was Hong Kong incorporated into China? How ancient is that?”, “Was the 1967 Riots a just struggle against colonial oppression or a violent campaign terrorising the public?”, “Did the colonial government ever offer democracy to Hong Kong?” More frequently, they use historical events to criticize or satirise current affairs. Meanwhile, some pages are being labelled as “blue pages”. They usually refer to pages sponsored by or affiliated to pro-government organisations. While a few of them focus on Hong Kong history, they generally lay emphasis on Chinese history, viewing Hong Kong history as an adjunct to national history. These pages usually avoid sensitive issues concerning the Chinese regime and perceive British colonial rule in a bad light. They also talk more about Hong Kong’s ancient history and highlight the close tie between Hong Kong and mainland China. In short, they assist the government to promote the official historical narrative. It is important to note that the definition for “yellow page” and “blue page” is vague and only a handful of pages openly declared their political stance. Many history pages are neither “yellow” nor “blue”.

What can I find in history pages? Tons of stuff! There are two kinds of “Hong Kong history” pages. The first kind surveys Hong Kong history as a whole and touches on multiple areas, while the second kind specialises in one or two subjects only. Most pages of the first kind focus on the modern history of Hong Kong, namely the city’s colonial past. Nevertheless, around ten pages look at Hong Kong’s ancient history. Among the latter pages, “Architecture and Historical Monuments” is the most popular subject, with fifteen pages specialising in it. Other popular subjects include “City Development” (such as the origin and planning of streets and neighbourhoods), “Military History”, and “Tradition and Culture”. Please refer to the “Main Content” column at my “History Pages, Channels, and Websites in Hong Kong” list for details.

The boom of Hong Kong’s history pages does not simply reflect Hongkongers’ rising interest in history. It also shows their will to take control of the past, no matter they are pro-government or pro-democracy. Through social media, history is no longer confined to universities, schools, museums, or even printed publications. Almost everyone can access history pages and basically everyone can create their own history page(s). Nevertheless, there are opportunities as well as challenges.

In Part 2 of this blogpost, Reynold will discuss the challenges and opportunities that these public history pages present us. Stay tuned!

[1] Please see the “Curriculum Framework of National Security Education in Hong Kong” for the latest official narrative on Hong Kong history and Chinese History (https://www.edb.gov.hk/tc/curriculum-development/kla/pshe/national-security-education/index.html).

[2] For older history pages, I would count the founding year of their parent organisations, as their websites may appear way earlier than their social media pages.

[3] Argued by Italian philosopher and historian Benedetto Croce in Theory & History of Historiography.

Andrew Hillier on Family and Memory in Old Hong Kong

We are pleased to have Dr. Andrew Hillier writing for us this week. After completing his PhD at the University of Bristol, Andrew is now an Honorary Research Associate at Bristol and regularly contributes to the University’s Historical Photographs of China project. Andrew has recently published his book Mediating Empire: An English Family in China 1817-1927 (huge congratulations Andrew!). He has kindly accepted our invite to write a blog post, in which he reflects on the impact of Hong Kong on three generations of his family.

Family and Memory in Old Hong Kong

‘Why didn’t I ask more about the family and the time it spent in Hong Kong and China?’ How often have I asked myself this question? However, in this post, I want to consider, not what I should have asked, but what earlier generations may and may not have asked about their forbears and their lives in Hong Kong. What they knew and what they were told will have informed the family’s collective memory, a memory that can be found embodied in their letters, photographs and surroundings and which, in turn, shaped their mind-set on both a public and private level.

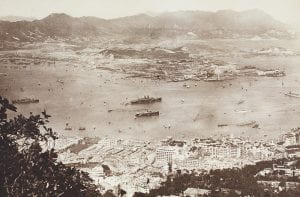

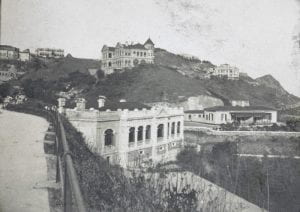

In 1895, Harry Hillier (my great- grandfather) was appointed Acting Commissioner of Imperial Maritime Customs (IMC) for Kowloon, and this was officially confirmed the following year. Although the Customs Stations were positioned on the China coast, the Commissioner was provided with a fine new residence on the Peak and there, for four years, Harry lived in exclusive luxury with his wife, Maggie, and four children – Eddie, his daughter by his first marriage, a second daughter, Dorothy, and two sons, Harold, my grand-father (born in 1892) and his younger brother, Geoff.[i]

This was not the first time Harry had lived in the colony. He was born there in February 1851 but the following year, his father, Charles Batten Hillier, the Colony’s Chief Magistrate, and his mother, Eliza, came to England, bringing with them Harry and his two elder brothers, Willie and Walter. When they returned to Hong Kong, the three boys were left to be cared for by a relative in Cambridge. But, if Harry had no actual memories of Hong Kong, he will have learned much about his parents’ life from the letters they wrote to him and his brothers, some of which still survive, and, later, from talking to his mother when she returned to England, following his father’s death in 1856.[ii]

We can get a good idea of the picture Eliza will have painted from the cache of letters, which she wrote to her sister, Martha, during her time in Hong Kong and which also still survive. Found in her papers when she died, they describe the colony’s early days when English families were beginning to settle and carve out a life, insulated from the teeming Chinese world on their doorstep, a genteel setting in which notions of imperial superiority and racial difference were already being forged.[iii]

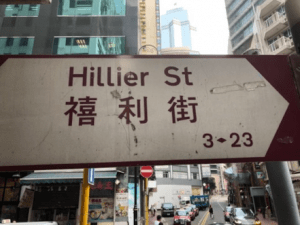

If these helped shape Harry’s mind-set, there were also two memorials which embodied his parents’ life in Hong Kong, one, very public, the other, intensely private, and both of which can still be found today. Hillier Street had been named as a parting gift by Governor Davis when he left in 1848, loathed by almost everyone, but not, it seems by Charles and the street remained an important family memorial.

Although his appointment as the colony’s Chief Magistrate in 1847 had come as ‘a bolt from the clouds’, and, over the next nine years, he would be subject to much criticism, when the time came to leave, he received fulsome plaudits for the way he had performed his duties. How much of this Harry will have learned by the time he arrived, we cannot know. Certainly, his mother will have focussed on the positive side and the colony will have been keen to forget this unhappy time in its history, which had culminated in the zealous but unbalanced Thomas Chisholm Anstey accusing almost all its officials, including Charles, of corruption.

However, Harry will certainly have learned about his father’s work shortly before he left, because it was then that James Norton-Kyshe published his monumental History of the Laws and Courts of Hong, with the first volume containing over one hundred references to Charles Hillier. If many were unflattering of this ‘noted flogger’, the final verdict, as delivered by the China Mail, was that, because of Charles’ ‘intimate knowledge of the Chinese language and Chinese customs, the Chinese would be unlikely to have again a Magistrate from whom they will receive as much justice’.[iv]

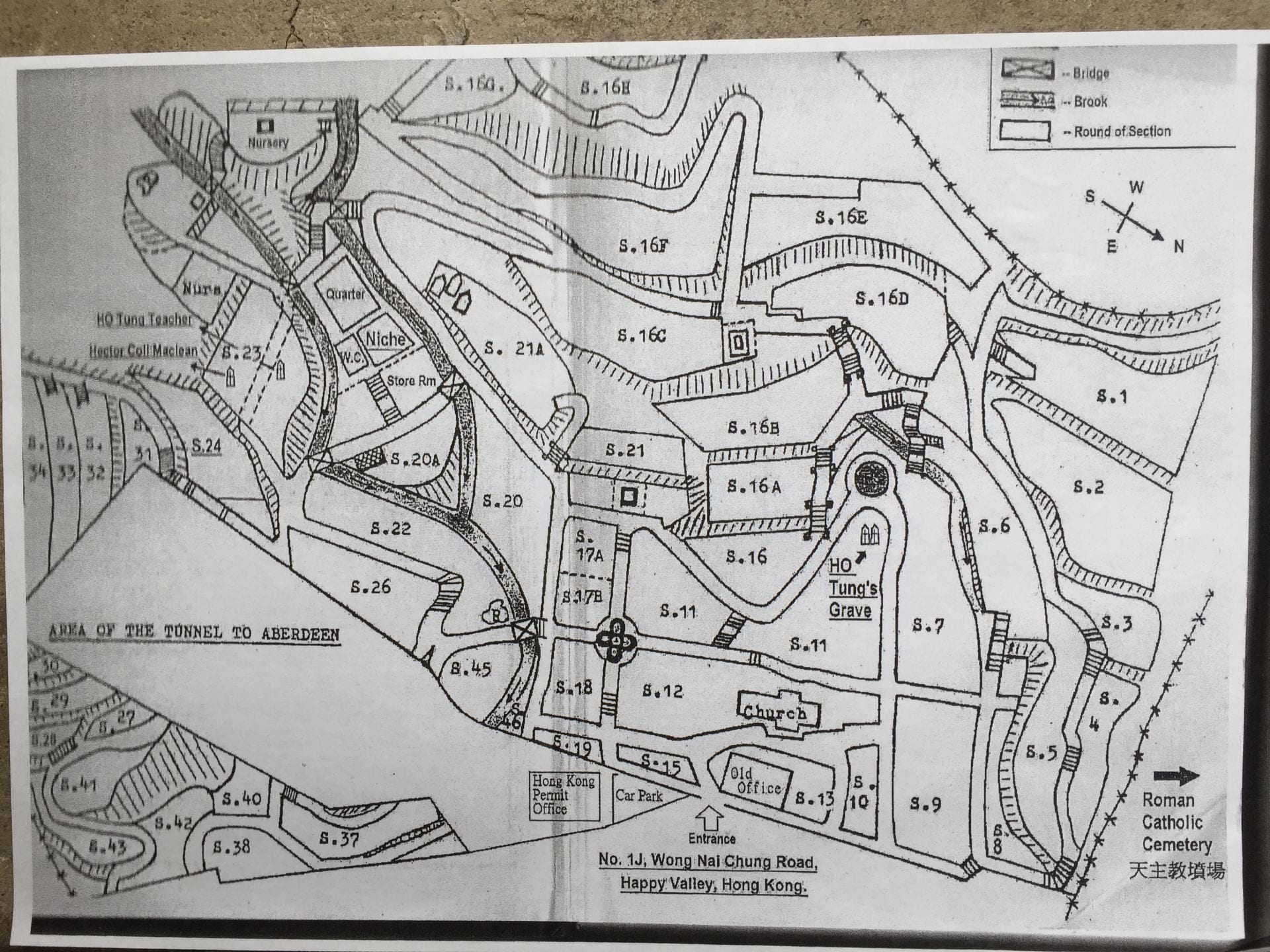

The second and intimate memorial is the single headstone of two of Charles’ and Eliza’s infant children, which can still be found in Happy Valley Cemetery. Whilst the death of Ann in 1847 will have meant nothing to Harry, that of little Hughie, who died in February 1856, must have done so at the time. Writing to the children in England, Eliza had proudly told them of his arrival, but the news was followed immediately afterwards by another letter from Charles, telling them ‘the sad tale’ of the death of ‘their little brother’. Again, both letters have survived and must have been kept as a memorial of these sad events. Even if Harry remembered little of the detail and did not visit the grave, there was enough here to conjure up his parents’ presence and memories of the separation that had so marked his early life.[v]

After three years enjoying Hong Kong’s cosmopolitan world, Harry’s life changed abruptly when, in 1898, Britain acquired and then the following year, forcibly took possession of the New Territories. His efforts to prevent the removal of the Customs stations were unsuccessful and, as Commissioner, he was strongly associated with the aggressive approach which culminated in large-scale slaughter of the protesters. Heavily criticised by the Chinese, in the view of Sir Robert Hart, the long-serving Inspector-General of the IMC, Harry had to be replaced. Whilst this was made easier by the fact he was due to go on furlough, these events left a bitter taste for him and Maggie, which was only partially mitigated by the eighteen months they spent on leave in Lausanne and England.

For his son, Harold, who was seven years old at the time, there was no bitterness – the time in Hong Kong had been, he later wrote, ‘marvellously happy’, one in which they had been able to indulge in all the privileges afforded to middle-class western children in this colonial setting. What was ‘harrowing’ was the parting with their father when his furlough ended and he returned to China alone. Harold well remembered, ‘making a resolve that never would I be in a position where I must periodically leave my family and go away alone’. [vi]

Separated for much of the next seven years until she returned to China, Harry and Maggie shared their anguish in their letters – some eighty during Harry’s two years in Shanghai – which can be found summarised in his Letters Book. These also reflected the difficulties Maggie was experiencing in bringing up two boys of spirit, who hardly saw their father over these years. By the time he returned in 1911, the children had left school, and nursing a bitterness about his final years in the Customs, he had little desire to talk about China. For Harold, therefore, Hong Kong evoked memories of pleasure but also of pain: the happiness of those years contrasting with the pangs of separation, in a way that would later colour his relations with his own children.

These memories are, therefore, captured in letters and photographs and embodied in lieux de memoire that can still be visited. It is still possible to walk down Hillier Street, to see the children’s grave-stone in Happy Valley Cemetery and to take the Peak tram to view the Commissioner’s house on Mount Kellet. And when I do so, I can reflect on what I should have asked my grandfather about his memories and about what his parents told him of their life in Hong Kong.

Mediating Empire was published in April 2020. My Dearest Martha: the Life and Letters of Eliza Hillier will be published in the autumn by Hong Kong City University Press. For details, see andrewhillier.org.

*Images used in this post with reference starting with ‘Hi-s’ are from the collections of the Historical Photographs of China Project at the University of Bristol.

[i] Detailed references for this post can be found in my book, Mediating Empire, An English Family in China. 1817-1927 (Folkestone: Renaissance Books, 2020).

[ii] Hillier Collection

[iii] The originals, together with typed transcripts are held at the School of Oriental and African Studies Archives, London (SOAS), CWM/LMS, MS 381124/01, Correspondence of Eliza Hillier.

[iv] James William Norton-Kyshe, The History of the Laws and Court of Hong Kong from the earliest period to 1898 (Hong Kong: Vetch and Lee Limited, 1898), Vol. 1, p. 384.

[v] For the gravestone, see the illustration in Patricia Lim, Forgotten Souls: A Social History of the Hong Kong Cemetery (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2011), p. 118. It is also referred to on http://Gwulo.com/node/8739, Inscriptions for Cemetery, Sections 01-09, Plot 09/08/18.

[vi] Harold Hillier, ‘Vita Mea’ (Hillier Collection), p. 9.

Vivian Kong on the Kowloon Residents Association and interwar Hong Kong’s civil society

Writing for our blog this week is our own Dr. Vivian Kong. Some of our readers may remember Vivian from when she was a PhD student with our Project. She finished her PhD thesis ‘Multiracial Britons: Britishness, Diasporas, and Cosmopolitanism in interwar Hong Kong’ in 2019, and is now a Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow in Hong Kong history at the University of Bristol. Vivian is now preparing a book manuscript on Britishness in 1910-45 Hong Kong, exploring how British colonialism, rising nationalism, and Asian cosmopolitanism affected the development of national, civic, urban, and diasporic identities in the city.

Writing for our blog this week is our own Dr. Vivian Kong. Some of our readers may remember Vivian from when she was a PhD student with our Project. She finished her PhD thesis ‘Multiracial Britons: Britishness, Diasporas, and Cosmopolitanism in interwar Hong Kong’ in 2019, and is now a Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow in Hong Kong history at the University of Bristol. Vivian is now preparing a book manuscript on Britishness in 1910-45 Hong Kong, exploring how British colonialism, rising nationalism, and Asian cosmopolitanism affected the development of national, civic, urban, and diasporic identities in the city.

On 24 January 1920 the South China Morning Post published a contributed article, ‘The New Kowloon: A Dream’. Set twenty years in the future, the piece depicted a Kowloon that was no longer ‘the foot-stool of the Peak’. Kowloon, in this ‘Dream’, was now a ‘large and prosperous city’ that had ‘large and luxurious hotels, a well-equipped European hospital, an up-to-date fire station, [and] houses to suit all pockets’. No longer did residents have to ‘bail surplus soda water in an endeavor to imitate a bath’: now the water supply ‘is never at fault’![1]

The anonymous author admitted this sounded ‘unreal’. And unreal it was for the many attendants at the inaugural meeting of the Kowloon Residents’ Association only four days prior. To these white-collar middle-class residents, the Kowloon of 1920 lacked the urban development it deserved. ‘Old Kowloon’, the section of Kowloon Peninsular south of Boundary Street, was ceded to Britain in 1860, and in 1898 Britain leased ‘New Kowloon’ as part of the New Territories for 99 years. Since the 1900s, Kowloon’s affordable rent made it a popular residential option for middle-class families in the colony. But urban development there, especially medical facilities and public transportation, did not grow accordingly to support its rapidly expanding population, an issue that began to receive increasing attention in the 1910s.

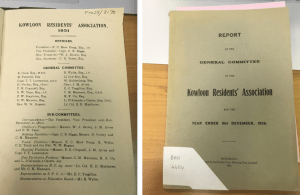

In December 1919, 122 residents in Kowloon came together to form a Kowloon’s Resident Association (KRA) to ‘periodically meet and discuss improvements in these districts with special regards to Housing, Lighting, Police, Communications, Sanitation, Water, etc.’.[2] The Association would grow steadily in the following years, and its membership would triple by 1931.

It was a multi-ethnic association. It was first known as 九龍西人居民協會 (meaning ‘Kowloon Westerner Residents’ Association’) because of its predominantly white leadership: between 1920 and 1925 most of its committee members were white, with the exception of a few Portuguese.[3] Some of KRA’s earlier activities also demonstrated racial prejudice against the Chinese population in the colony. They had, for instance, suggested the formation of another European residential reservation in Kowloon to enforce racial segregation.[4] But things changed in 1926 when three prominent Chinese residents, S. W. Tso, B. Wong Tape, and Wong Kwong-tin joined the executive Committee. The Association had its first Chinese vice-president in 1928, and three years later, F. C. Mow Fung, a returned Australian Chinese became its first Chinese president. The 379 members of its 1931 membership had at least 85 Chinese, 6 Eurasians, 58 Macanese, 1 Filipino, 3 Parsi, and 5 Jews. Of these 379 members, 13 were women.

These members worked together to pressure the government for more public works in Kowloon. They met regularly to discuss issues of concern to the neighborhood. They criticized government policies. They drafted proposals for public works needed and approached relevant government departments. They acted as an advisory body for the colonial government and helped officials solicit public opinion – in 1938, for example, they asked all Kowloon residents to send them answers to a questionnaire for the Rents Commission.[5] Results of KRA activities were evident: after its lobbying, the government introduced a motor bus service in Kowloon in 1921, enlarged the area’s postal service, and opened the Kowloon Hospital in 1925.[6]

But facilitating urban development was not their only objective: they also wanted political reform for Hong Kong. They formed the Association not only because they wanted to pressure the government to develop Kowloon, but to have a say on how precisely it would do so. The KRA’s founding president, B. L. Frost, made this clear in his inaugural speech: ‘We want more representation and better representation on the Legislature’.

Frost was a Bristolian: he was born and raised there, and he was in fact, like myself, a Bristol University graduate.[7] But Frost was also a Hong Kong-Briton: he had lived in Hong Kong since 1905. This was unusual, as it was estimated that the non-Chinese population would renew almost completely every five years.[8] As a long-term resident, Frost thought the government did not act in the interest of middle-class residents like himself. He criticized the fact that the authorities had only ‘three quite inadequate sources of information’: its own staff, unofficial members in the Legislative Council – many taipans of big hongs – and ‘wealthy landowners’. He hoped that the KRA, with the weight of more than a hundred members joining even before its official formation, would make their voices heard by the government.[9]

This was why the author of the ‘New Kowloon: A Dream’ article aspired that the KRA would have, ‘like the worms, turned and made Kowloon’s voice heard above the levels of the Peak’.

But were their voices heard?

Yes, and no. As stated earlier, the KRA did manage to get the government to speed up its development of Kowloon. With regards to its political demands, they had asked repeatedly for a Kowloon representative in the Legislative Council, which they eventually did get. In 1929, Governor Sir Cecil Clementi added two unofficial seats to the Legislative Council, one representing the Chinese community and the other Kowloon residents. The two appointees for these seats, S. W. Tso and J. P. Braga, were both KRA members.[10]

But the KRA also wanted a municipal government. As early as October 1920, only ten months after its formation, the KRA urged the government to form a Kowloon Municipal Council to celebrate the jubilee of Kowloon as a British territory.[11] This proposal was not successful, but they were persistent. In 1930, even after Tso and Braga were appointed to the Legislative Council, they did not forget and asked the government again for a municipal council.[12]

Such a hope, however, remained unanswered for years. Even when in 1936, the government replaced the Sanitary Board with the Urban Council and enlarged its powers, only two of the eight unofficial members were elected, with the governor appointing all other seats. It was not until 1994 that Hong Kong had its first municipal council election, where all seats were elected based on universal suffrage. But even that didn’t last long: the Urban Council was disbanded after the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong in 1997.

As a historian of interwar urban Asia, researching the KRA has been enlightening: it offers a case study of how a middle-class identity drove multi-ethnic urbanites together to fight for not only the betterment of their neighbourhood, but also their political rights. That much of its membership overlapped with other civic associations in Hong Kong was also interesting, for it suggests that interwar Hong Kong had a nexus of middle-class individuals who, despite colonial Hong Kong’s constitutional limits, used voluntary societies with different purposes to shape their society.

As a Hong Konger, I find it important to think about the KRA too. We had often assumed that Hong Kong was somewhere that had ‘no politics but only administration’, but the KRA shows that even as those in Hong Kong did not push harder for electoral politics, they were not politically apathetic. I reflected in my latest journal article how claims KRA members made in the 1920s about widening political representation and constitutional reforms still sit at the heart of the ongoing protests. I pondered why most demands the KRA members made about political reforms failed. I also find it refreshing to see the value that multi-culturalism brought to the city’s development. Hong Kong is a multi-ethnic city; it always has been.

Vivian has recently published findings from her research on the KRA and other voluntary associations in interwar Hong Kong (the Rotary Club, Freemasonry, and the League of Fellowship) in an article ‘Exclusivity and Cosmopolitanism: Multi-Ethnic Civil Society in Interwar Hong Kong’ in the Historical Journal.

[1] ‘The New Kowloon: A Dream’, South China Morning Post (SCMP), 24 January 1920.

[2] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association: To be formed for discussing improvements’, Hongkong Daily Press, 2 December 1919; ‘Kowloon Residents Association: Formed Last Night’, SCMP, 2 December 1919.

[3] ‘九龍居民協會敘會 [Kowloon Residents’ Association Meeting]’, 香港華字日報 [The Chinese Mail], 24 March 1922.

[4] See ‘Kowloon Residents Association: Yesterday’s Inaugural Meeting’, SCMP, 21 January 1920, p. 8; ‘Kowloon Residents Association: Plea for a European Reservation’, Hongkong Daily Press, 13 February 1923, p. 5.

[5] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association’, SCMP, 10 March 1938, p. 2.

[6] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association: Plea for a European Reservation’, Hongkong Daily Press, 13 February 1923; ‘Kowloon Residents Association: The Housing Question, Kowloon Hospital, and Post Office Facilities’, SCMP, 13 February 1923, p. 9.

[7] ‘Old Time Resident Leaving: Mr. Frost retires after 21 years here, K.R.A. Tribute’, SCMP, 26 June 1926.

[8] J. D. Lloyd, ‘Report on the Census of the Colony of Hong Kong 1921’, Sessional Papers laid before the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, 15 December 1921 p. 159.

[9] ‘Kowloon Residents Association: Yesterday’s inaugural meeting’, SCMP, 21 January 1920; ‘Kowloon Residents: To form an association’, Hongkong Telegraph, 2 December 1919.

[10] ‘No. 226 Appointments’, Hongkong Government Gazette, 3 May 1929, p. 166.

[11] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association: Year’s work reviewed, recommendation for municipal council’, China Mail, 5 October 1920.

[12] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association: President’s able summary of a successful year’s work’, Hongkong Daily Press, 1 March 1930.

Introducing Florence Mok

This week we have a contribution by Dr. Florence Mok, whose article ‘Public Opinion Polls and Covert Colonialism in British Hong Kong’ in China Information has recently been awarded the Eduard B. Vermeer Prize (congratulations Dr. Mok!). We first met Florence at the University of York, where she completed her PhD on state-society relations in colonial Hong Kong. Now a postdoctoral fellow in the History Department at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Florence has kindly accepted our invite to tell us about her academic journey, and her current projects.

History has always been my passion. I still remember reading my first history book when I was nine. Since then, I have aspired to become a historian. I completed both my BA and MA in Durham University. Prior to my PhD, I specialized in early modern English history. My MA thesis examined Royalism and Royalists during the English Civil War from 1642-1651. The period is fascinating. It witnessed some uncontrollable violence but also the emergence of numerous radical ideas. The world was indeed ‘turned upside down’. As a Hong Kong native, I always found Hong Kong history interesting and wanted to explore how state-society relations evolved from time to time. Inspired by the Umbrella Movement in 2014, I decided to shift my research focus from early modern England to contemporary Hong Kong. I was intrigued by the rise of political activism and wanted to investigate the historical roots of increased political mobilizations and changing political culture in Hong Kong.

History has always been my passion. I still remember reading my first history book when I was nine. Since then, I have aspired to become a historian. I completed both my BA and MA in Durham University. Prior to my PhD, I specialized in early modern English history. My MA thesis examined Royalism and Royalists during the English Civil War from 1642-1651. The period is fascinating. It witnessed some uncontrollable violence but also the emergence of numerous radical ideas. The world was indeed ‘turned upside down’. As a Hong Kong native, I always found Hong Kong history interesting and wanted to explore how state-society relations evolved from time to time. Inspired by the Umbrella Movement in 2014, I decided to shift my research focus from early modern England to contemporary Hong Kong. I was intrigued by the rise of political activism and wanted to investigate the historical roots of increased political mobilizations and changing political culture in Hong Kong.

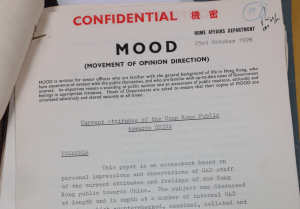

During my PhD at the University of York, I was supervised by Dr. David Clayton. My PhD thesis examined the relationship between political culture and policy making in British Hong Kong in the long 1970s. Existing scholarship has not addressed the impact of political mobilizations on new administrative, legislative and institutional changes, and the link between political attitudes and social classes. This field remains dominated by the theoretical work of political scientists and sociologists, and is therefore weakly supported by empirical evidence drawn from archival sources. My thesis explored how a reformist colonial administration investigated Chinese political culture, and how activism by social movements in Hong Kong impacted policy making. It investigated how the colonial state monitored public opinion through covert opinion polling exercises, namely Town Talk and MOOD, and how Chinese communities engaged in political movements and discourses, providing a long-term perspective of the constitutional crisis in Hong Kong today. The content was organized using five case studies of social movements/policy making: the Chinese as the official language movement, the anti-corruption campaign, the campaign against telephone rate increases, the Precious Blood Golden Jubilee Secondary School disputes and immigration from Mainland China.

The thesis argued that the colonial administration possessed increased organizational capacity to monitor the movement of opinion direction in the Chinese society closely. Shifting from indirect rule to the City District Officer Scheme, it invested in its surveillance apparatus in the 1970s. Two covert opinion polling exercises, Town Talk and MOOD, were introduced. These constructed ‘public opinions’ were circulated and discussed among high ranked civil servants, including the Governor and policy makers in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. They affected policy formulation in subtle ways. Hong Kong people had extremely limited democratic rights but the public was involved in the policy making process. The thesis also highlighted how ‘public opinion’ was a construction, and how political cultures in Hong Kong varied in accordance with class and age, and changed in significant ways. For example, the upper class believed that political activism was undignified and undermined political stability. The working class, driven by instrumentalism, distanced themselves from social movements. However, in general, the Chinese communities demonstrated increased readiness to engage in political movements and discourses in the 1970s. I have published the preliminary findings of my thesis as a journal article in China Information.

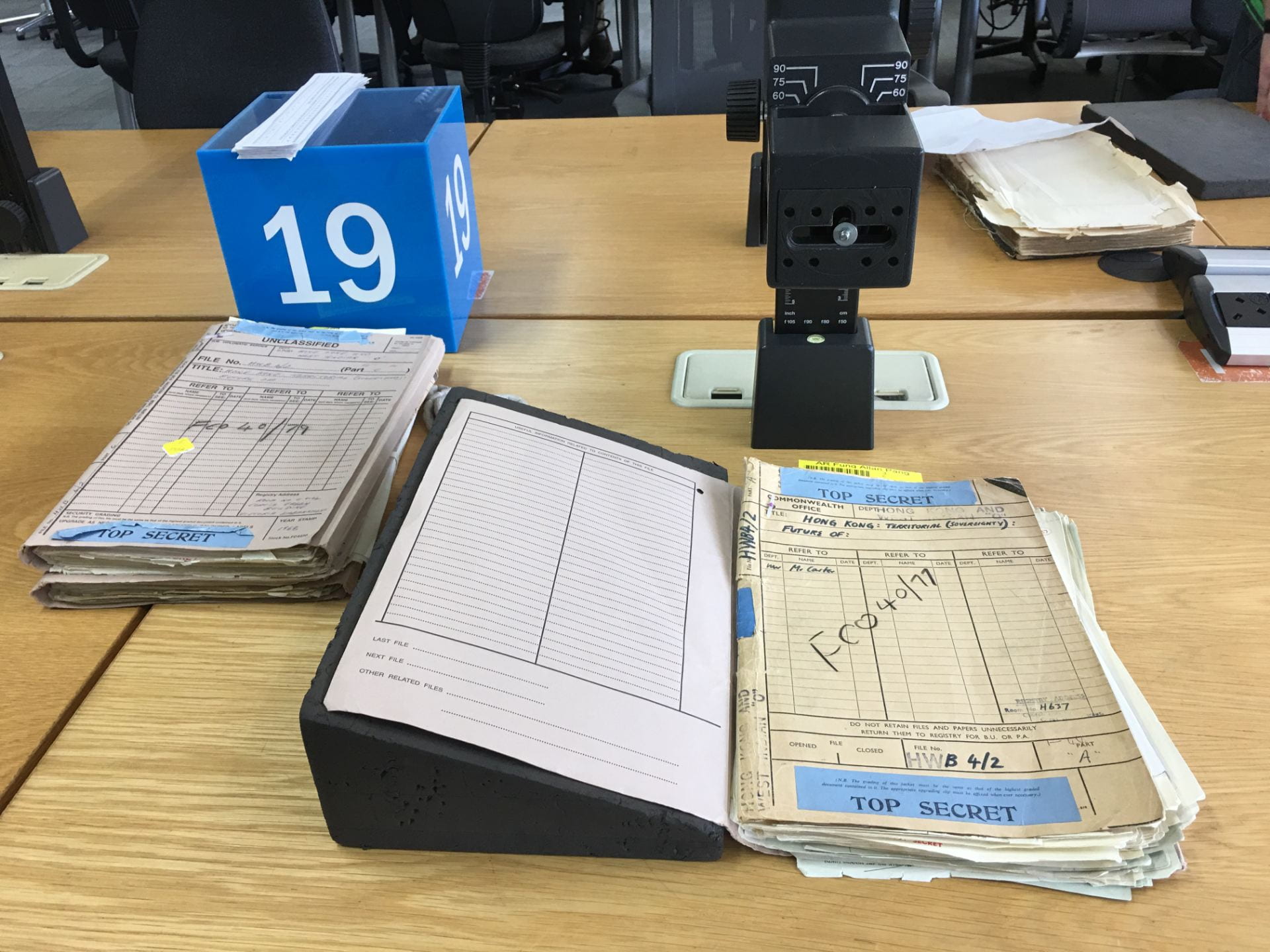

After completing my PhD, I started working as a postdoctoral fellow in the History Department at Nanyang Technological University in October 2019. I am currently working on two different projects. My postdoctoral project examined Chinese Communist cultural activities in colonial Hong Kong, a pivot in the Cold War, from 1949-1980. It focuses on the four modes of communication used by the Chinese Communists to propagate the Communist regime and expand their influence in the colony: the press, literature, ‘traditional’ cultural activities and school education. The main objective is to investigate through different channels, how the Communists infiltrated Hong Kong society, and to observe how the colonial government countered these activities without, in theory, compromising the concept of ‘the rule of law’. The unexplored primary data in the National Archives in London and the Public Record Office in Hong Kong is rich. The ‘migrated’ Foreign Office Archives are a new source of material. These documents include 110 categories concerning Hong Kong, many of which are related to the organization of sensitive British intelligence and the containment of communism in the colony. This data, which has only come to light in the last few years due to the efforts of lawyers, journalists and historians, will transform our understanding of British colonial history. This study will shed light on the current constitutional crisis in Hong Kong by tracing past Communist activities in the colony and deconstructing the concept and practice of ‘the rule of law’, which is commonly recognized by Hong Kong people as a British legacy.

My second project is a collaboration with my former supervisor, David Clayton. The project focuses on water emergency in Hong Kong in 1963-64. Hong Kong suffered from unprecedented shortages of water then, due to insufficient rain, rapid economic development and under-investment in the water infrastructure. Access to water was rationed, placing severe burdens on Hong Kong households, especially women who had to queue, carry and store water. Our project examines how individuals and social groups responded to these privations, and how this crisis altered their relationship with the colonial state. We are going to assess the level and form of complaints and explain these observations in terms of (i) everyday cultural practices and (ii) a contingent factor: how the crisis was managed by agencies of the colonial states. The project will contribute to environment and social histories of water management, which, hitherto, have focused on rural droughts.

Introducing Kelvin Chan

We are thrilled to have Kelvin Chan contributing to our blog this week. A PhD student at McGill University, Kelvin gave a fascinating presentation in our conference in June this year in Hong Kong about the repatriation of mental health patients in Hong Kong from the 1870s to the 1920s. Interested to know more about his wider project on the history of psychiatry and mental health in Hong Kong and China, we therefore invited him to tell us more about his PhD research on our blog.

I received my BA degree of history in HKBU in 2017, and a master’s degree in international history in LSE in 2018. In my undergraduate study, I had the freedom to explore different topics that have shaped my current research interest, such as the history of Indian sailors, prostitutes, venereal diseases, and colonialism. To me, these topics centre on the changing definitions of “deviance”, which lie at the heart of my research about the history of mental health.

I received my BA degree of history in HKBU in 2017, and a master’s degree in international history in LSE in 2018. In my undergraduate study, I had the freedom to explore different topics that have shaped my current research interest, such as the history of Indian sailors, prostitutes, venereal diseases, and colonialism. To me, these topics centre on the changing definitions of “deviance”, which lie at the heart of my research about the history of mental health.

Under the supervision of Professor David Wright, I am planning to focus on the history of psychiatry and mental health asylums in my PhD research. Broadly speaking, my research focus will be the Mental Health Asylums in Hong Kong and John Kerr Refuge in Canton, which were established in the late 19th century and operated by foreigners.

When I was writing my undergraduate dissertation about Lock Hospitals and venereal diseases in Shanghai, I came across a lot of documents about lunatic asylums. These institutions confined the patients in a separate space and alienated them from society through diseases. Reading these documents makes me curious about the history of mental health in China, and particularly the history of the Castle Peak Hospital (青山醫院). I guess many Hongkongers have a similar perception about the Castle Peak Hospital as a remote or somehow horrifying institution in the past.

However, unlike the US and Europe with a very well documented history of mental health, the institutions in Hong Kong and modern China have received relatively little attention from historians. Perhaps it was because of the hidden nature of treating patients at home in Chinese society. It is essential to mention that the idea of insanity and confining mental health patients in an institution was foreign to Chinese culture before the late 19th century. The second reason might be related to the specific role of asylums in Hong Kong that the colonial Government tended to repatriate the patients to Canton and to their countries of origin instead of providing treatment. Lastly, the archives about these institutions are dispersed and sporadic. So there is an apparent lack of understanding of these institutions, especially the one in Hong Kong.

Since the project is still in a preliminary stage, I mostly visited the archive in the UK and Hong Kong. The materials related to the mental asylums are relatively dispersed, so my archives include the government gazette, asylums’ annual reports, records of repatriation from the colonial and foreign office, and missionary records. I will also look at the archives from the Kerr Refuge and other asylums in China as a point of reference. These records have led me to reconstruct the history of mental health through a case study of Hong Kong and Canton. More importantly, it also looks at the trans-colonial context in which repatriation of patients was also a common practice in colonial port cities.

The most surprising finding of my research is the transnational perspective of asylums in Hong Kong. Medical officers in colonies, such as India, often viewed treatment as the solution of handling the insane. The case of Hong Kong shows another understudied perspective of the history of mental health. Colonial Government denied most of the responsibilities in handling this group of undesirable population – usually lower class, sailors, paupers without family support.

Repatriation, therefore, was one of the favourable solutions. It allowed the Government to draw a clear boundary to define who belonged to Hong Kong, and who did not. In many case files I read, Chinese who had resided in Hong Kong for a decade was still not considered a “Hong Kong” citizen. They would repatriate them to Canton for treatment. At the same time, the colonial Government would repatriate European patients to their countries of origin. They sent the European patients to the foreign embassies in Hong Kong, who were very likely to reject European patients’ identity documents such as visa and passport. Foreign insane, in other words, were dumped in Hong Kong and became “stateless”. After all, the colonial Government had to take care of them, and how to handle them became constant trouble.

Although my research is still preliminary, I think it points to some directions that help us better understand the history of Hong Kong. First, the history of mental health tells us more about colonial governance. The confinement of the mentally disturbed defined deviant behaviour in early Hong Kong. On some levels, it severed as a tool of control of the Government. But at the same time, the asylums reflected the dilemmas faced by colonial authorities in which the Government struggled to handle and repatriate the “foreign” patients.

Second, the history of mental health allows us to explore the policies of immigration control in the context of the British Empire and colonial Hong Kong. Until recently, scholars urge to pay attention to the colonial legislation on immigration restriction in which insanity played an important role. Similarly, the colonial Government in Hong Kong introduced a series of laws to regulate the movement of the insane in the 1890s and 1900s, such as the Imbecile Person Introduction Ordinance in 1903. Examining the migration legislation and regulation sheds light on the global history of regulating the transient population.

Introducing Adonis Li

Our guest writer this week is Adonis Li, PhD student at the University of Hong Kong. We first met Adonis in 2016 when the Project visited the University of York, where Adonis did his BA and MA, for a symposium on Hong Kong history. Our paths have crossed often since: in January this year Adonis spoke at our postgraduate workshop about his earlier work on Sir Percy Cradock and the future of Hong Kong, and in June we met in Hong Kong again, where we heard that he is now working on another project that is also very relevant to the daily lives of Hong Kongers – the history of the city’s public transport. Adonis kindly accepted our invite to tell us more about his research here, and explained how his interest about history shifted from the ‘Horrible Histories’ series of children’s books and historical video games to the modern history of Hong Kong.

History was one of my favourite subjects in school, not least because of the popular Horrible Histories series of children’s books. The sense of humour and the ‘gory bits’ of the series taught me that history doesn’t have to be just lists of kings and queens and great deeds. Instead, history could talk about how both elites and regular people lived. Yet, as time went on and topics of study narrowed due to exam requirements, I found myself increasingly disillusioned with what I was studying. Modern history, in particular twentieth-century history, was all that my high school taught. I grew tired of regurgitating the same information over and over again, perhaps once from the British perspective, then again from the American perspective, then German, Soviet, French and so on. Thankfully, I continued to receive good grades in the subject.

History was one of my favourite subjects in school, not least because of the popular Horrible Histories series of children’s books. The sense of humour and the ‘gory bits’ of the series taught me that history doesn’t have to be just lists of kings and queens and great deeds. Instead, history could talk about how both elites and regular people lived. Yet, as time went on and topics of study narrowed due to exam requirements, I found myself increasingly disillusioned with what I was studying. Modern history, in particular twentieth-century history, was all that my high school taught. I grew tired of regurgitating the same information over and over again, perhaps once from the British perspective, then again from the American perspective, then German, Soviet, French and so on. Thankfully, I continued to receive good grades in the subject.

I managed to keep up my interest in history during this period through historical video games. Series such as Age of Empires and Total War mixed strategy, city building and medieval history together into one fun yet difficult package. I would eventually find myself spending more time reading the introductions to different historical factions and events than playing the actual games. I remember thinking ‘if only school would teach us medieval history and not the Second World War!’

I then went to the University of York, where I obtained a BA (Hons) in History and an MA in Contemporary History and International Politics. Aside from its location close to my home in Leeds and the campus’s beautiful brutalist architecture, I chose York because of its rich medieval past. During my second year there, I lived a few metres away from its medieval city walls (though unfortunately I ended up with nosy tourists peering into my windows every afternoon). I fulfilled my wishes of studying medieval history by enrolling in early medieval courses; the first seminar I ever attended was on the course titled ‘Goths and Romans’.

However, alongside Goths, Romans and Vikings, I also enrolled on modern history courses. I became increasingly interested in my place of birth, Hong Kong, and wanted to know more about its past. The Umbrella Movement of 2014 coincided with the start of my studies at York, and I chose courses on the history of the British Empire and on Chinese history. There were weeks where I would juggle reading translated Latin texts with reading translated Chinese texts, then trying to look up the original source of the latter. Over time (and with a dissertation proposal deadline looming), I came to realise that though medieval history is incredibly interesting (and fun!), modern history was a better subject of serious study for me personally.

I worked with David Clayton, Senior Lecturer at York, to complete my BA dissertation on the visit of Governor Murray MacLehose to Beijing in 1979, which started the negotiations over Hong Kong’s transfer of sovereignty. I then wrote an MA dissertation on the role of Sir Percy Cradock during and after these negotiations, using documents from his papers collection.

My original plan was to write a PhD thesis on another facet of the negotiations. However, I had become interested in something that was, and still is, very important for Hongkongers and city-dwellers all over the world; public transport.

Through websites such as CityMetric and Facebook groups such as New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens, I started to look at my own commutes and usage of public transport critically. It turns out there’s more to it than just complaining about two buses coming at once after a long wait. Behind every journey were histories of mobility, political negotiations, financial considerations, and social changes. Once I had moved to Hong Kong, I had very contrasting experiences to compare, between commuting on the underfunded, aging northern English rail-lines and on the largely punctual and clean Mass Transit Railway.

The line I spend most of my time on, the East Rail Line, was once called the Kowloon-Canton Railway. It was completed in 1910 and was Hong Kong’s first heavy rail line, one that withstood war, regime changes and takeover by the MTR Corporation. It has been ever-present in Hong Kong’s modern history. Yet, very little academic history has been written on the Kowloon-Canton Railway. My project will be the first to do so.

My project looks at the history of the railway from different perspectives. I will use official sources from the National Archives in Kew and the Public Records Office in Kwun Tong. I will also use unofficial ones, such as travel guides and newspapers. If there’s one thing that has been a constant amongst commuters over the past century, it’s complaining about their mode of transportation. Of course, I am open to any suggestions on other potential sources.

As well as plugging a gap in histories written about Hong Kong, my research can also tell us how railway problems of the past were overcome, perhaps providing lessons on how to overcome present issues. The construction of the line was late and over-budget. Trains suffered from poor punctuality and overcrowding. Overzealous fare collectors caused issues. Policing and border control demanded resources. Fare increases were invariably met with passenger disgruntlement.

Sound familiar? These issues could have been chosen from 1919, 1969, or 2019. In a city so heavily reliant on its rail network, a look at its history is needed.

Introducing Allan Pang

We are delighted to have Allan Pang writing for us this month. Currently an MPhil student at the University of Hong Kong, Allan spoke in our conference in June about his research on the promotion of Cantopop and colonial Chineseness. We were fascinated by his research and therefore invited him to tell us a bit more about his wider research on our blog.

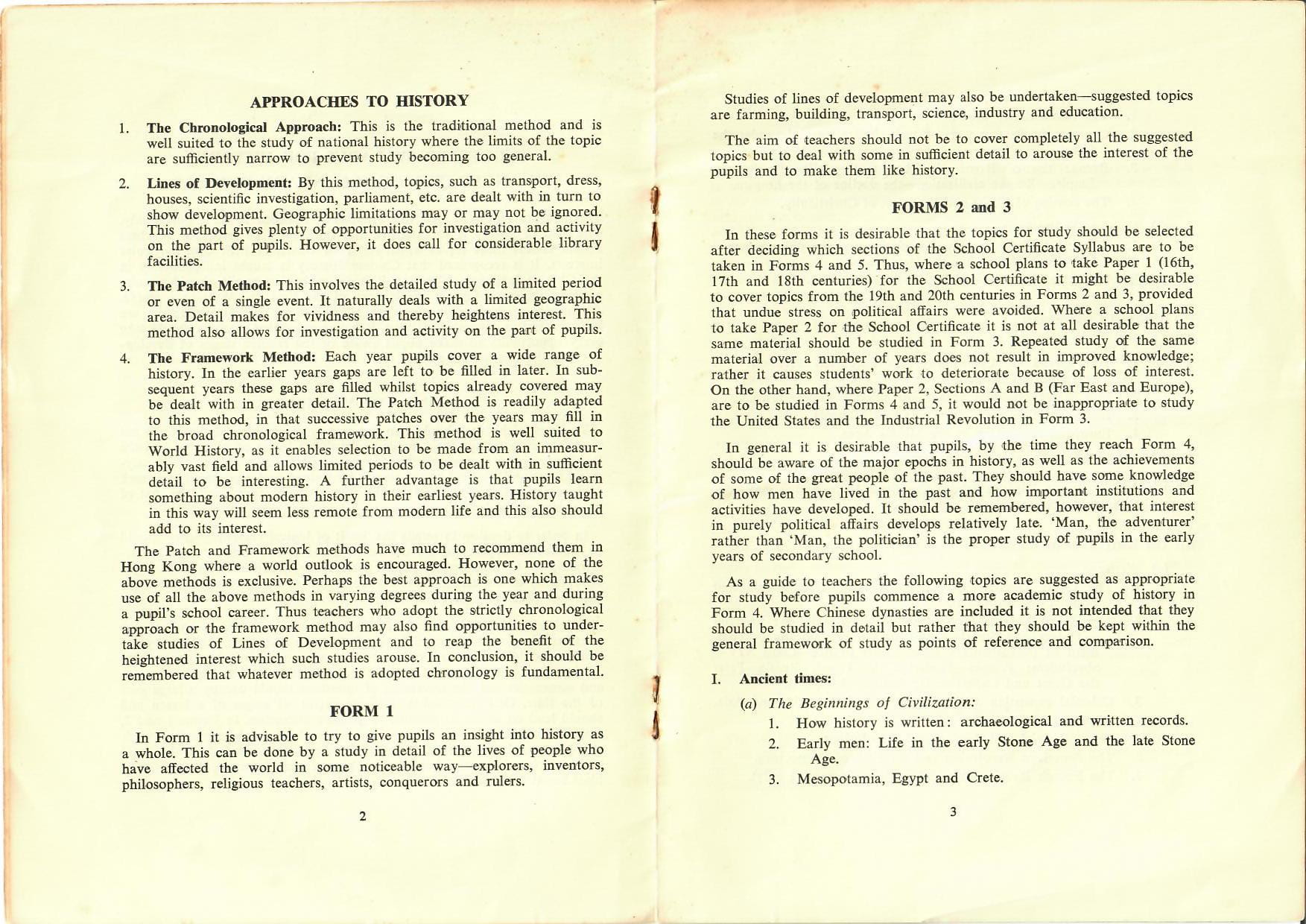

Unlike other contributors to the HKHP blog, I do not have an intriguing story of how I became interested in my research topics. I took history in my secondary school, chose history as my (only) major during my BA at HKU, and decided to pursue an MPhil in history. I became loyal to this subject because it gives me the autonomy that I can never experience while taking courses in other disciplines.I could criticise my history textbooks and the syllabus in class when I was a secondary school student, and I could choose whatever topic for my essays at the university. Eventually, I started to research the histories of things that I am interested in, such as popular music, history education, and postage stamps in my home – Hong Kong. When I was a school kid, I enjoy searching for old news reports to find out details about the concerts that I like (though they usually took place before I was born), flipping through outdated history textbooks and syllabuses, and finding out how the old Lunar New Year postage stamps look like. I thought I was simply gossiping about insignificant items in my life (or in Cantonese baat gwaa 八卦). But thanks to my teachers at the History Department of HKU, I realised I can turn all these into my research topics.

My MPhil thesis examines how the colonial government attempted to promote, shape, or even control Chineseness in Hong Kong from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. It analyses colonial policies from three perspectives: language, festivals, and objects. My study starts with policies on the Chinese language. Inspired by the revolutionary spirit of the Cultural Revolution in mainland China, youth in Hong Kong started the Chinese Language Movement to demand an official status of the Chinese language. To pacify the activists, the government superficially reformed its language policies by introducing the Official Language Ordinance and slow changes in government operation. My thesis then focuses on festivities. Officials promoted both traditional and modern Chineseness to pacify people across generations. To achieve this aim, they promoted traditional Chinese festivals in the colony. They also held the Festival of Hong Kong and numerous variety shows (including those featuring traditional and popular music). My study also examines policies on various objects: postage stamps, commemorative coins, and monuments. The government sold postage stamps and coins that showcase Hong Kong’s traditional Chinese culture to people within and without the colony. Officials also preserved and promoted Chinese monuments to locals and tourists.

I started my research with government records in The National Archives in Kew and the Public Records Office in Hong Kong. As official documents cannot reveal the whole story and part of them are always missing, I also consulted materials from various university libraries and archives. The Hong Kong Collections at HKU provide numerous official publications during the colonial era. I also utilised materials from the Hong Kong Tourism Board Collection. Its brochures and leaflets illustrate how the Hong Kong Tourist Association helped promote Chinese monuments from the late 1970s on. Hong Kong collections in the Hoover Institution Archives also provide useful materials. Various personal papers, such as the James Hayes Papers, John Walden Collection, and Michael Kirst Papers, contain official documents and correspondence which help me understand several social policies, especially those related to the Chinese language. I also visited the Weston Library at the University of Oxford to consult transcripts of interviews with former colonial officials. These interviews reveal how several high-ranking officials, including governors, made their decisions.

I became interested in this topic because but it reveals how the colonial state utilised culture as a tool of control (while it also brings together items that amuse me!). Through these cultural policies, Governor Murray MacLehose attempted to foster the local population’s sense of belonging by Chinese standards. His government tried to promote Hong Kong not only as a better place to live but also an authentic Chinese city in order to make local Chinese people, especially the younger generation, consider Hong Kong as their home. I also hope to link this period of Hong Kong history to the international situation, such as the cultural aspect of the Cold War and international tourism.

At the same time, I am researching two other topics on Hong Kong history. The first one is the development of history education since the 1950s. This project will explore how the state utilised the past to stabilise (and later decolonise) Hong Kong and construct colonial legacies. Through this research, I also hope to expand the concept of history education beyond syllabuses and textbooks to include museums, monuments, and festivals. This study will also examine Hong Kong’s transnational linkages to other former parts of the British Empire in Southeast Asia. The second topic is the history of local popular music. The global dimension to Hong Kong’s popular music also deserves our attention. I hope to show that popular music other than Cantopop, such as English pop, was also significant globally even while Cantopop was in its age of glory. In other words, I would like to explore the history of a “global Hong Kong Pop.”

Researching my Hong Kong family’s past: A fourteen-year quest [Part 3]

RESEARCHING MY HONG KONG FAMILY’S PAST:

A FOURTEEN-YEAR QUEST

(Part 3)

by an anonymous contributor

One of my first stops in Hong Kong was St Michael’s Catholic Cemetery in Happy Valley, where my English grandfather had been buried in 1923. The grave records were not on line, but I had the number of his grave and a photograph of the original. I understand that the cemetery register can now be found through www.familysearch.org although I have not tried this out myself. Even if you do not have a grave number, the cemetery office has a complete plan of all the graves and a record of names. They are happy to guide bona fide relatives. When we first arrived the cemetery warden was on his siesta and I tried unsuccessfully to find my grandfather’s grave by myself. By the time we met up with the cemetery warden it was nearly dusk. The front of my grandfather’s grave was hidden by an overhanging tree. The following year I took out a new lease on the grave and was able to get it straightened and cleaned. St Michael’s is so crowded that some of the older graves are being removed to make room for new ones. There is a list of fixed charges for grave renovation displayed outside the cemetery office. I had to sign a form declaring that I was entitled to arrange the renovation and take an oath to that effect in a notary’s office in town. The cemetery warden introduced me to their trusted contractors and I paid half their fee in cash up front. When they had finished, they sent me a photo of the final grave and I sent them a banker’s draft for the remainder.

For the Protestant Cemetery next door to St. Michael’s, the office has a map to guide you to the various sections. Patricia Lim’s database of the cemetery’s inscriptions on Gwulo.com will supply the appropriate Section, row and number, if you search by name. Instructions as to how to search are given at https://gwulo.com/node/8746 The cemetery office will supply a map of the cemetery and, in the past, a cemetery worker has helped me to find an elusive grave.

The specialist ex-Hong Kong researcher and lecturer, Christine M. Thomas, has taken meticulous photographs of every single grave in the Protestant Cemetery and compiled many stories about their occupants. For a small charge she will provide a photograph and directions to a grave. The transferred grave of my great-grandparents’ first baby is not recorded on Lim’s database, and I would not have been able to find it without Christine Thomas’s guidance. Some of the gravestones are blackened or have fallen face down, making things even more difficult. Pollution is fast causing erosion of lettering on the stones and some of the inscriptions have become illegible even in the fourteen years since I first visited the cemeteries. Christine Thomas’s details can be found at http://www.agra.org.uk/christine-thomas-specialist-researcher-in-somerset and this is the link to her interesting blog http://hongkongcemetery.blogspot.com

I have been lucky enough to accompany my husband on business trips to Hong Kong, but never for more than three or four days at a time per year. It is not a methodology I would recommend, but the most practical available to me. I have spent most of my time at the Public Records Office in Kwun Tong https://www.grs.gov.hk/en/online_holdings.html

The PRO can be contacted directly and have just upgraded their online catalogue. The old Rate Books, which are not on line, are held there. These are invaluable for verifying property ownership and addresses for the years up till 1934. They are very large and not more than six may be ordered at any one time. Each volume covers one year, or in some cases, half a year. There is a printed index which can be ordered on site.

Up till December 2018, the invaluable Carl Smith index cards could only be consulted on the Public Records Office’s premises, but digital images of the cards have now been put online, which is a huge new benefit to researchers. The 139,922 double-sided data cards were compiled from newspapers, wills and church records by the late Reverend Carl Smith. The link is https://search.grs.gov.hk/en/searchcarladv.xhtml?rpp=10.

The original cards were donated by the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong to the Central Library where they can be consulted with special prior permission from the RASHK librarian. Arranged in alphabetical order, the cards are too fragile to be photocopied but can be copied by hand on the spot. Each row of drawers has to be separately unlocked by a member of staff on request.

The journals of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong branch provide fascinating background material on a variety of subjects. The SOAS library holds a run of the journals up to 2008.

The link to search the old Hong Kong Newspapers is https://mmis.hkpl.gov.hk/web/guest/old-hk-collection?from_menu=Y&dummy. Although rewarding, it is a time consuming process unless you know the precise dates to search. To search for precise dates the format is with inverted commas e.g. “1900-01-01”.

Gwulo.com gives an oral tutorial about how to search the old newspapers for a word or a phrase https://gwulo.com/node/36666 Gwulo also publishes a useful list of “Quick Links” on “How to find Hong Kong’s History”.

The so-called “Blue Books” contain information on anyone whose salary was paid by the government. The National Archive at Kew in London holds original copies from 1844 to 1940, grouped under the reference CO 133. You can also search historical passenger lists through ancestry.com at the National Archive without paying their subscription. The Blue Books from 1871 to 1940 are now on line at the HKGRO website.

I have had mixed results from the Land Registry, Queensway Government Offices, 19/F, 66 Queensway. I have visited them twice together with a Chinese friend to find out the purchase and sale dates of various properties owned by my great-grandfather and grandfather at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth. Armed with the original Inland Lot numbers on my first visit, I got copies of all the purchase and sale dates of the properties I wanted, at the end of an hour. But it was hard going for the person helping us and I felt I would not have got anywhere without the persuasiveness of my friend and his fluent Cantonese. On my more recent visit the less experienced and less cooperative counter person was unwilling to undertake a historical search to match up the old Inland Lot numbers with present day addresses. I ended up paying the fee she demanded for printouts and received records that did match the I.L. numbers that I wanted, but were now attached to different addresses. From her eagerness to get rid of me, I am convinced my “helper” knew the addresses were not the original ones.

The Lands Department has upgraded its website to enable online ordering, which means that you no longer have to go to its office at North Point. I went there a couple of years ago with a companion who knew the ropes. I was able to access aerial photographs of different dates of the area where my grandfather had lived and of his house, now long since demolished. I had the option of ordering a copy of these, which could be collected within 24 hours, or an enhanced version, which would not be ready for four days. I also bought a very detailed 1920s map of the area. I do not know whether it is now possible to order from abroad with a credit card or whether a bankers draft is necessary. There is a tutorial on how to access their maps service at https://gwulo.com/node/41760.

Some old Hong Kong maps are also held by the British Library in London and can be photographed without charge for personal use.

If you have academic affiliation you can also use the extensive resources of the Hong Kong University Library and SOAS Library in London.

World War 2 scattered many Hong Kong families, including mine, and my quest has taken me both to Canada and Australia. My grandmother must have been evacuated from Hong Kong, but there was a “Whites Only” policy in Australia in 1940-41 and she may have been turned back at Manila. There is no record of her name on the lists researched by Tony Banham for his book on the Hong Kong evacuation, Reduced to a Symbolical Scale, which means she may have sailed privately. I have found no record of her between 1926 and 1941 in Hong Kong, nor in Australia until the 1954 census. The Sydney telephone book turned out to be an invaluable resource for tracing the descendants of the niece who signed her death certificate. There were only five entries for the niece’s married name, but I had a 100% return to my five answerphone messages. These led me from one person to the next and finally, via New Zealand, to a surviving cousin, who sadly died during an operation very soon after I spoke to her. I learnt valuable information from two long telephone conversations with her and later with her sister. Do not be afraid of cold calling. The telephone has been my friend.

As well as tracking the upward path of my English grandfather’s Hong Kong company in the first two decades of the twentieth century, my narrative will record what I have learnt about my “hidden” Eurasian grandmother, who outlived all but one of her five children. Despite the efforts of her close family to erase her very existence, the story of my quest will pick out the small pieces of evidence that bear witness to her life. I hope it will serve as a slight memorial to her.

I also hope that some of the above information will be useful to others researching their Hong Kong past, whether amateurs or academics. Websites are improving all the time and there will be more and more available online. Good luck to all!

Some resources: a shortlist

Hong Kong Genealogical Forum

British Library, London, UK

The National Archive, Kew, UK

SOAS library and photo archive

Public Records Office, Hong Kong

Carl Smith’s Index Cards (now online)

Patricia Lim’s database of graves in the Protestant Cemetery, Happy Valley

Christine M. Thomas, Private researcher and specialist in Hong Kong genealogy

St Michael’s Catholic Cemetery and the Catholic Church

Births, Deaths & Marriages Dept., Low Block, 66 Queensway, Hong Kong

Land Registry, 66 Queensway, High Block, Hong Kong.

Lands Department, 333 Java Road, North Point, Hong Kong