We are delighted to have Allan Pang writing for us this month. Currently an MPhil student at the University of Hong Kong, Allan spoke in our conference in June about his research on the promotion of Cantopop and colonial Chineseness. We were fascinated by his research and therefore invited him to tell us a bit more about his wider research on our blog.

Unlike other contributors to the HKHP blog, I do not have an intriguing story of how I became interested in my research topics. I took history in my secondary school, chose history as my (only) major during my BA at HKU, and decided to pursue an MPhil in history. I became loyal to this subject because it gives me the autonomy that I can never experience while taking courses in other disciplines.I could criticise my history textbooks and the syllabus in class when I was a secondary school student, and I could choose whatever topic for my essays at the university. Eventually, I started to research the histories of things that I am interested in, such as popular music, history education, and postage stamps in my home – Hong Kong. When I was a school kid, I enjoy searching for old news reports to find out details about the concerts that I like (though they usually took place before I was born), flipping through outdated history textbooks and syllabuses, and finding out how the old Lunar New Year postage stamps look like. I thought I was simply gossiping about insignificant items in my life (or in Cantonese baat gwaa 八卦). But thanks to my teachers at the History Department of HKU, I realised I can turn all these into my research topics.

My MPhil thesis examines how the colonial government attempted to promote, shape, or even control Chineseness in Hong Kong from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. It analyses colonial policies from three perspectives: language, festivals, and objects. My study starts with policies on the Chinese language. Inspired by the revolutionary spirit of the Cultural Revolution in mainland China, youth in Hong Kong started the Chinese Language Movement to demand an official status of the Chinese language. To pacify the activists, the government superficially reformed its language policies by introducing the Official Language Ordinance and slow changes in government operation. My thesis then focuses on festivities. Officials promoted both traditional and modern Chineseness to pacify people across generations. To achieve this aim, they promoted traditional Chinese festivals in the colony. They also held the Festival of Hong Kong and numerous variety shows (including those featuring traditional and popular music). My study also examines policies on various objects: postage stamps, commemorative coins, and monuments. The government sold postage stamps and coins that showcase Hong Kong’s traditional Chinese culture to people within and without the colony. Officials also preserved and promoted Chinese monuments to locals and tourists.

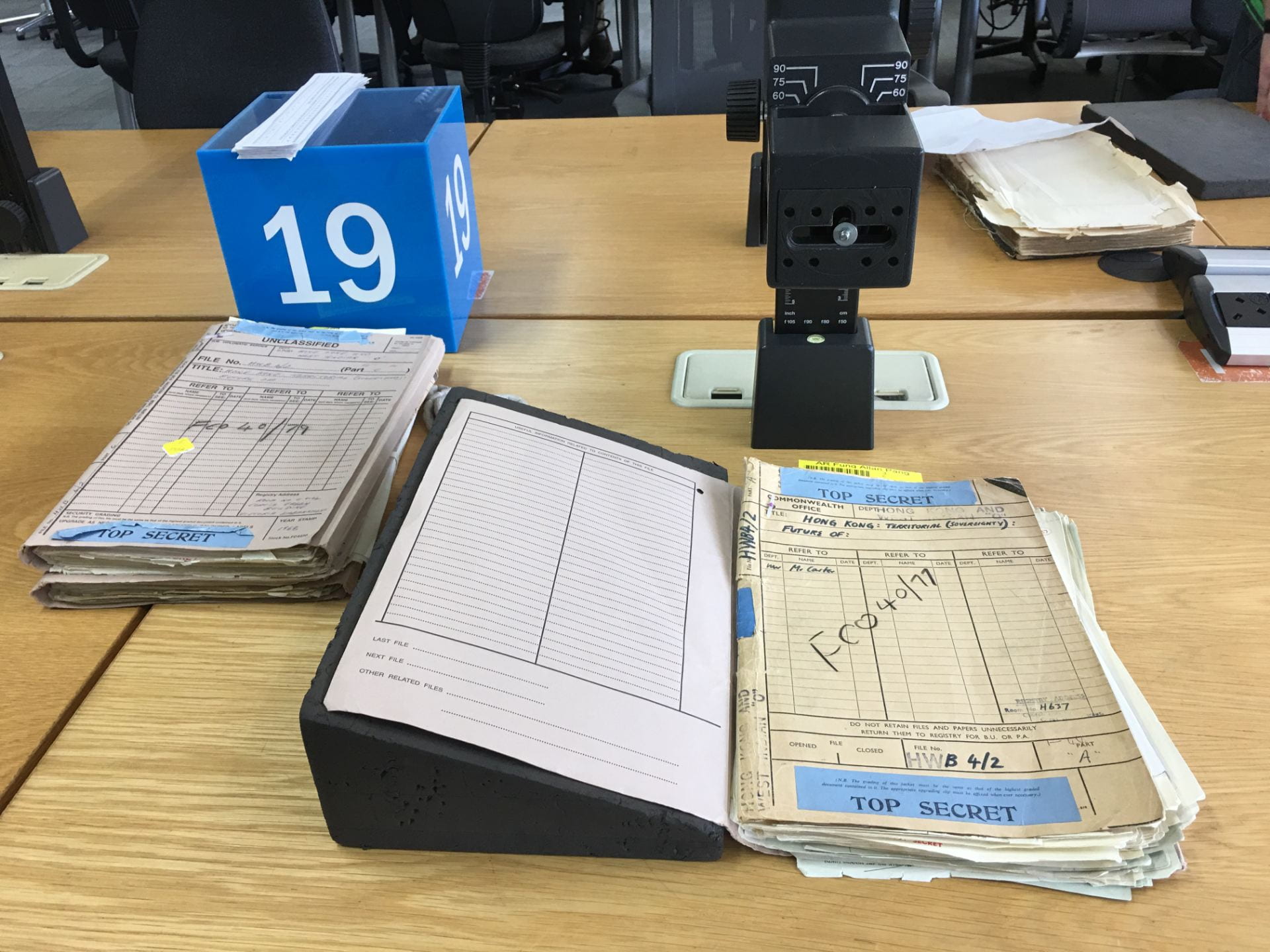

I started my research with government records in The National Archives in Kew and the Public Records Office in Hong Kong. As official documents cannot reveal the whole story and part of them are always missing, I also consulted materials from various university libraries and archives. The Hong Kong Collections at HKU provide numerous official publications during the colonial era. I also utilised materials from the Hong Kong Tourism Board Collection. Its brochures and leaflets illustrate how the Hong Kong Tourist Association helped promote Chinese monuments from the late 1970s on. Hong Kong collections in the Hoover Institution Archives also provide useful materials. Various personal papers, such as the James Hayes Papers, John Walden Collection, and Michael Kirst Papers, contain official documents and correspondence which help me understand several social policies, especially those related to the Chinese language. I also visited the Weston Library at the University of Oxford to consult transcripts of interviews with former colonial officials. These interviews reveal how several high-ranking officials, including governors, made their decisions.

I became interested in this topic because but it reveals how the colonial state utilised culture as a tool of control (while it also brings together items that amuse me!). Through these cultural policies, Governor Murray MacLehose attempted to foster the local population’s sense of belonging by Chinese standards. His government tried to promote Hong Kong not only as a better place to live but also an authentic Chinese city in order to make local Chinese people, especially the younger generation, consider Hong Kong as their home. I also hope to link this period of Hong Kong history to the international situation, such as the cultural aspect of the Cold War and international tourism.

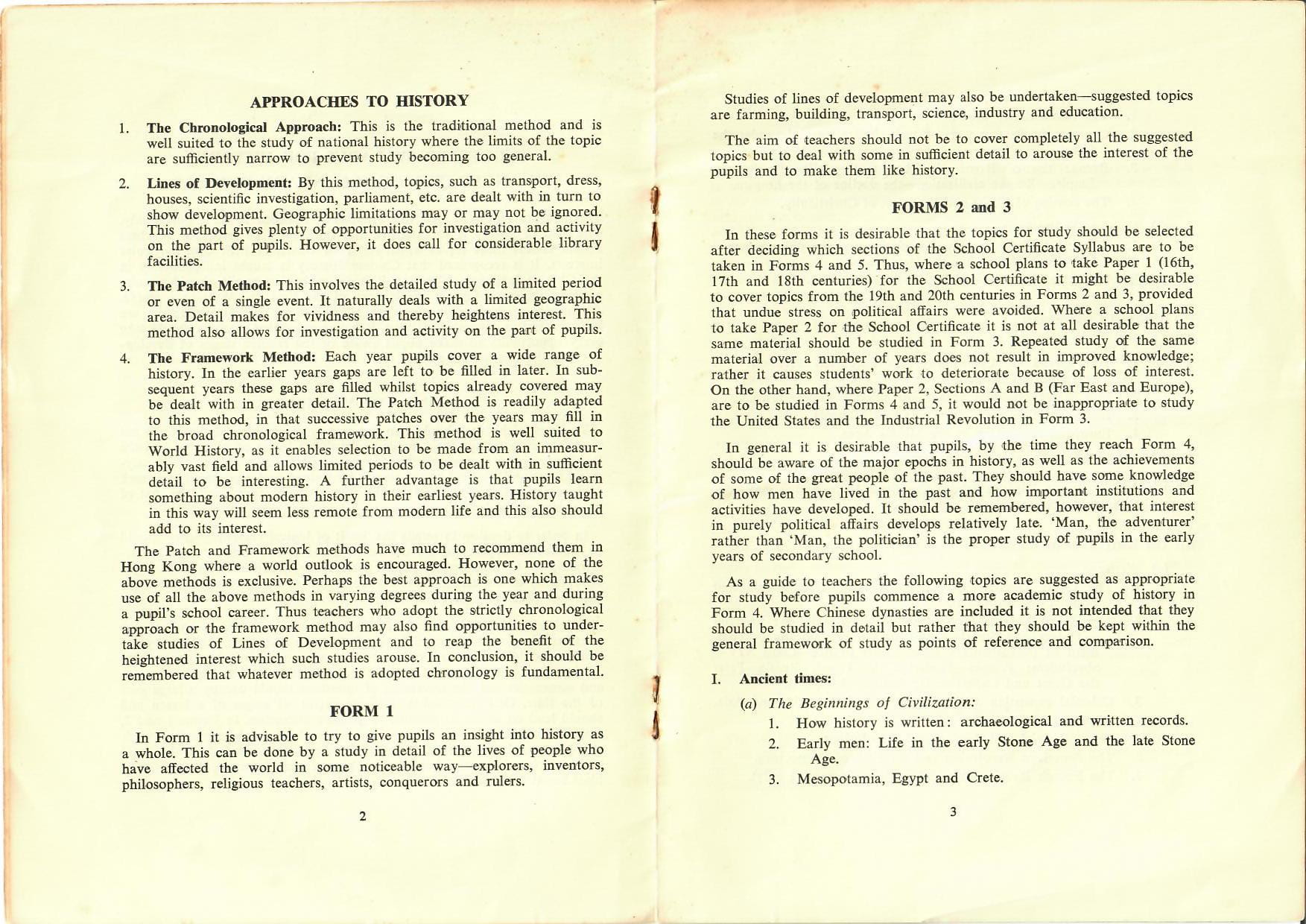

Suggested Syllabus for History in Anglo-Chinese Secondary Schools (1964 Edition). Hong Kong: Government Printer, 1964.

At the same time, I am researching two other topics on Hong Kong history. The first one is the development of history education since the 1950s. This project will explore how the state utilised the past to stabilise (and later decolonise) Hong Kong and construct colonial legacies. Through this research, I also hope to expand the concept of history education beyond syllabuses and textbooks to include museums, monuments, and festivals. This study will also examine Hong Kong’s transnational linkages to other former parts of the British Empire in Southeast Asia. The second topic is the history of local popular music. The global dimension to Hong Kong’s popular music also deserves our attention. I hope to show that popular music other than Cantopop, such as English pop, was also significant globally even while Cantopop was in its age of glory. In other words, I would like to explore the history of a “global Hong Kong Pop.”