Writing for our blog this week is our own Dr. Vivian Kong. Some of our readers may remember Vivian from when she was a PhD student with our Project. She finished her PhD thesis ‘Multiracial Britons: Britishness, Diasporas, and Cosmopolitanism in interwar Hong Kong’ in 2019, and is now a Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow in Hong Kong history at the University of Bristol. Vivian is now preparing a book manuscript on Britishness in 1910-45 Hong Kong, exploring how British colonialism, rising nationalism, and Asian cosmopolitanism affected the development of national, civic, urban, and diasporic identities in the city.

Writing for our blog this week is our own Dr. Vivian Kong. Some of our readers may remember Vivian from when she was a PhD student with our Project. She finished her PhD thesis ‘Multiracial Britons: Britishness, Diasporas, and Cosmopolitanism in interwar Hong Kong’ in 2019, and is now a Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow in Hong Kong history at the University of Bristol. Vivian is now preparing a book manuscript on Britishness in 1910-45 Hong Kong, exploring how British colonialism, rising nationalism, and Asian cosmopolitanism affected the development of national, civic, urban, and diasporic identities in the city.

On 24 January 1920 the South China Morning Post published a contributed article, ‘The New Kowloon: A Dream’. Set twenty years in the future, the piece depicted a Kowloon that was no longer ‘the foot-stool of the Peak’. Kowloon, in this ‘Dream’, was now a ‘large and prosperous city’ that had ‘large and luxurious hotels, a well-equipped European hospital, an up-to-date fire station, [and] houses to suit all pockets’. No longer did residents have to ‘bail surplus soda water in an endeavor to imitate a bath’: now the water supply ‘is never at fault’![1]

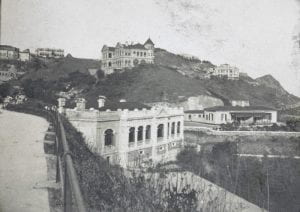

The anonymous author admitted this sounded ‘unreal’. And unreal it was for the many attendants at the inaugural meeting of the Kowloon Residents’ Association only four days prior. To these white-collar middle-class residents, the Kowloon of 1920 lacked the urban development it deserved. ‘Old Kowloon’, the section of Kowloon Peninsular south of Boundary Street, was ceded to Britain in 1860, and in 1898 Britain leased ‘New Kowloon’ as part of the New Territories for 99 years. Since the 1900s, Kowloon’s affordable rent made it a popular residential option for middle-class families in the colony. But urban development there, especially medical facilities and public transportation, did not grow accordingly to support its rapidly expanding population, an issue that began to receive increasing attention in the 1910s.

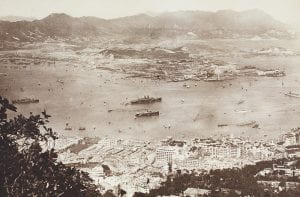

Tsim Sha Tsui 尖沙咀 c. 1925. University of Bristol Historical Photographs of China Project, Ref Bk09-05.

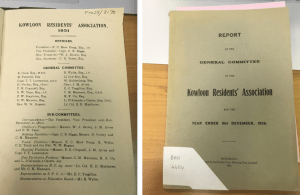

In December 1919, 122 residents in Kowloon came together to form a Kowloon’s Resident Association (KRA) to ‘periodically meet and discuss improvements in these districts with special regards to Housing, Lighting, Police, Communications, Sanitation, Water, etc.’.[2] The Association would grow steadily in the following years, and its membership would triple by 1931.

It was a multi-ethnic association. It was first known as 九龍西人居民協會 (meaning ‘Kowloon Westerner Residents’ Association’) because of its predominantly white leadership: between 1920 and 1925 most of its committee members were white, with the exception of a few Portuguese.[3] Some of KRA’s earlier activities also demonstrated racial prejudice against the Chinese population in the colony. They had, for instance, suggested the formation of another European residential reservation in Kowloon to enforce racial segregation.[4] But things changed in 1926 when three prominent Chinese residents, S. W. Tso, B. Wong Tape, and Wong Kwong-tin joined the executive Committee. The Association had its first Chinese vice-president in 1928, and three years later, F. C. Mow Fung, a returned Australian Chinese became its first Chinese president. The 379 members of its 1931 membership had at least 85 Chinese, 6 Eurasians, 58 Macanese, 1 Filipino, 3 Parsi, and 5 Jews. Of these 379 members, 13 were women.

The 1931 and 1936 annual reports of the Kowloon Residents Association at the National Library of Australia.

These members worked together to pressure the government for more public works in Kowloon. They met regularly to discuss issues of concern to the neighborhood. They criticized government policies. They drafted proposals for public works needed and approached relevant government departments. They acted as an advisory body for the colonial government and helped officials solicit public opinion – in 1938, for example, they asked all Kowloon residents to send them answers to a questionnaire for the Rents Commission.[5] Results of KRA activities were evident: after its lobbying, the government introduced a motor bus service in Kowloon in 1921, enlarged the area’s postal service, and opened the Kowloon Hospital in 1925.[6]

But facilitating urban development was not their only objective: they also wanted political reform for Hong Kong. They formed the Association not only because they wanted to pressure the government to develop Kowloon, but to have a say on how precisely it would do so. The KRA’s founding president, B. L. Frost, made this clear in his inaugural speech: ‘We want more representation and better representation on the Legislature’.

Frost was a Bristolian: he was born and raised there, and he was in fact, like myself, a Bristol University graduate.[7] But Frost was also a Hong Kong-Briton: he had lived in Hong Kong since 1905. This was unusual, as it was estimated that the non-Chinese population would renew almost completely every five years.[8] As a long-term resident, Frost thought the government did not act in the interest of middle-class residents like himself. He criticized the fact that the authorities had only ‘three quite inadequate sources of information’: its own staff, unofficial members in the Legislative Council – many taipans of big hongs – and ‘wealthy landowners’. He hoped that the KRA, with the weight of more than a hundred members joining even before its official formation, would make their voices heard by the government.[9]

Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon. (Source: University of Bristol – Historical Photographs of China Project. Ref: FH01-281.)

This was why the author of the ‘New Kowloon: A Dream’ article aspired that the KRA would have, ‘like the worms, turned and made Kowloon’s voice heard above the levels of the Peak’.

But were their voices heard?

Yes, and no. As stated earlier, the KRA did manage to get the government to speed up its development of Kowloon. With regards to its political demands, they had asked repeatedly for a Kowloon representative in the Legislative Council, which they eventually did get. In 1929, Governor Sir Cecil Clementi added two unofficial seats to the Legislative Council, one representing the Chinese community and the other Kowloon residents. The two appointees for these seats, S. W. Tso and J. P. Braga, were both KRA members.[10]

But the KRA also wanted a municipal government. As early as October 1920, only ten months after its formation, the KRA urged the government to form a Kowloon Municipal Council to celebrate the jubilee of Kowloon as a British territory.[11] This proposal was not successful, but they were persistent. In 1930, even after Tso and Braga were appointed to the Legislative Council, they did not forget and asked the government again for a municipal council.[12]

Such a hope, however, remained unanswered for years. Even when in 1936, the government replaced the Sanitary Board with the Urban Council and enlarged its powers, only two of the eight unofficial members were elected, with the governor appointing all other seats. It was not until 1994 that Hong Kong had its first municipal council election, where all seats were elected based on universal suffrage. But even that didn’t last long: the Urban Council was disbanded after the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong in 1997.

As a historian of interwar urban Asia, researching the KRA has been enlightening: it offers a case study of how a middle-class identity drove multi-ethnic urbanites together to fight for not only the betterment of their neighbourhood, but also their political rights. That much of its membership overlapped with other civic associations in Hong Kong was also interesting, for it suggests that interwar Hong Kong had a nexus of middle-class individuals who, despite colonial Hong Kong’s constitutional limits, used voluntary societies with different purposes to shape their society.

As a Hong Konger, I find it important to think about the KRA too. We had often assumed that Hong Kong was somewhere that had ‘no politics but only administration’, but the KRA shows that even as those in Hong Kong did not push harder for electoral politics, they were not politically apathetic. I reflected in my latest journal article how claims KRA members made in the 1920s about widening political representation and constitutional reforms still sit at the heart of the ongoing protests. I pondered why most demands the KRA members made about political reforms failed. I also find it refreshing to see the value that multi-culturalism brought to the city’s development. Hong Kong is a multi-ethnic city; it always has been.

Vivian has recently published findings from her research on the KRA and other voluntary associations in interwar Hong Kong (the Rotary Club, Freemasonry, and the League of Fellowship) in an article ‘Exclusivity and Cosmopolitanism: Multi-Ethnic Civil Society in Interwar Hong Kong’ in the Historical Journal.

[1] ‘The New Kowloon: A Dream’, South China Morning Post (SCMP), 24 January 1920.

[2] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association: To be formed for discussing improvements’, Hongkong Daily Press, 2 December 1919; ‘Kowloon Residents Association: Formed Last Night’, SCMP, 2 December 1919.

[3] ‘九龍居民協會敘會 [Kowloon Residents’ Association Meeting]’, 香港華字日報 [The Chinese Mail], 24 March 1922.

[4] See ‘Kowloon Residents Association: Yesterday’s Inaugural Meeting’, SCMP, 21 January 1920, p. 8; ‘Kowloon Residents Association: Plea for a European Reservation’, Hongkong Daily Press, 13 February 1923, p. 5.

[5] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association’, SCMP, 10 March 1938, p. 2.

[6] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association: Plea for a European Reservation’, Hongkong Daily Press, 13 February 1923; ‘Kowloon Residents Association: The Housing Question, Kowloon Hospital, and Post Office Facilities’, SCMP, 13 February 1923, p. 9.

[7] ‘Old Time Resident Leaving: Mr. Frost retires after 21 years here, K.R.A. Tribute’, SCMP, 26 June 1926.

[8] J. D. Lloyd, ‘Report on the Census of the Colony of Hong Kong 1921’, Sessional Papers laid before the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, 15 December 1921 p. 159.

[9] ‘Kowloon Residents Association: Yesterday’s inaugural meeting’, SCMP, 21 January 1920; ‘Kowloon Residents: To form an association’, Hongkong Telegraph, 2 December 1919.

[10] ‘No. 226 Appointments’, Hongkong Government Gazette, 3 May 1929, p. 166.

[11] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association: Year’s work reviewed, recommendation for municipal council’, China Mail, 5 October 1920.

[12] ‘Kowloon Residents’ Association: President’s able summary of a successful year’s work’, Hongkong Daily Press, 1 March 1930.

![Researching my Hong Kong family’s past: A fourteen-year quest [Part 3]](https://www.hkhistory.net/files/2019/07/IMG_4941-e1563874954902-150x150.jpg)