RESEARCHING MY HONG KONG FAMILY’S PAST:

A FOURTEEN-YEAR QUEST

PART 2

by an anonymous contributor

With the burden of the family research now in my hands, I decided I would put an enquiry about our family on the Hong Kong …

28/05/19

RESEARCHING MY HONG KONG FAMILY’S PAST:

A FOURTEEN-YEAR QUEST

(Part 1)

by an anonymous contributor

Vivian Kong has asked me to share my experience of researching my Hong Kong family’s past. As a graduate of Bristol University, I am more …

22/04/19

We are excited to announce that registration for our ‘“All Roads Lead to Hong Kong”: People, City, Empires’ conference is now open here. The conference will take place at the University of Hong Kong on 6-7 June. We welcome any …

18/04/19

This week our guest writer is Meng (Stella) Wang, PhD candidate at University of Sydney. Stella’s research interests lie in the history of childhood, particularly on children’s everyday life, their use of urban space, and the formation of their identity …

03/02/19

Happy new year everyone! We are delighted to have Tim Yung as our first guest writer in 2019. A PhD candidate at the University of Hong Kong, Tim’s research concerns South China Anglican Identity in the early twentieth century. Here’s …

13/01/19

Call for Papers

Hong Kong History Project Post-Graduate Workshop

University of Bristol, January 2019

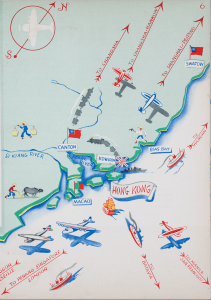

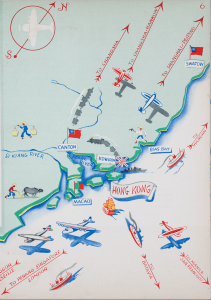

‘Hong Kong and Beyond: Mapping the City’s Networks’

The Hong Kong History Project at the University of Bristol is pleased to announce its third Postgraduate Workshop, …

06/11/18

We are glad to have Vivien Chan as our contributor this week. Vivien is a design historian based in London. She is currently a PhD candidate on the Cultures of Occupation in Twentieth Century Asia Project at University of Nottingham, …

22/10/18

Our guest writer this week is Shuang Wu, PhD student at the University of Hong Kong and King’s College, London. Shuang’s research explores lives of Chinese mothers in colonial Hong Kong and the United Kingdom after the Second World …

30/09/18

“All Roads Lead to Hong Kong”: People, City, Empires

Hong Kong History Project Conference

6-7 June 2019, University of Hong Kong

Keynote speaker: Henry Yu, Associate Professor, Department of History, University of British Columbia

28/09/18RESEARCHING MY HONG KONG FAMILY’S PAST:

A FOURTEEN-YEAR QUEST

PART 2

by an anonymous contributor

With the burden of the family research now in my hands, I decided I would put an enquiry about our family on the Hong Kong …

28/05/19

RESEARCHING MY HONG KONG FAMILY’S PAST:

A FOURTEEN-YEAR QUEST

(Part 1)

by an anonymous contributor

Vivian Kong has asked me to share my experience of researching my Hong Kong family’s past. As a graduate of Bristol University, I am more …

22/04/19We are excited to announce that registration for our ‘“All Roads Lead to Hong Kong”: People, City, Empires’ conference is now open here. The conference will take place at the University of Hong Kong on 6-7 June. We welcome any …

18/04/19This week our guest writer is Meng (Stella) Wang, PhD candidate at University of Sydney. Stella’s research interests lie in the history of childhood, particularly on children’s everyday life, their use of urban space, and the formation of their identity …

03/02/19Happy new year everyone! We are delighted to have Tim Yung as our first guest writer in 2019. A PhD candidate at the University of Hong Kong, Tim’s research concerns South China Anglican Identity in the early twentieth century. Here’s …

13/01/19

Call for Papers

Hong Kong History Project Post-Graduate Workshop

University of Bristol, January 2019

‘Hong Kong and Beyond: Mapping the City’s Networks’

The Hong Kong History Project at the University of Bristol is pleased to announce its third Postgraduate Workshop, …

06/11/18We are glad to have Vivien Chan as our contributor this week. Vivien is a design historian based in London. She is currently a PhD candidate on the Cultures of Occupation in Twentieth Century Asia Project at University of Nottingham, …

22/10/18Our guest writer this week is Shuang Wu, PhD student at the University of Hong Kong and King’s College, London. Shuang’s research explores lives of Chinese mothers in colonial Hong Kong and the United Kingdom after the Second World …

30/09/18

“All Roads Lead to Hong Kong”: People, City, Empires

Hong Kong History Project Conference

6-7 June 2019, University of Hong Kong

Keynote speaker: Henry Yu, Associate Professor, Department of History, University of British Columbia

28/09/18