Our guest writer this week is Shuang Wu, PhD student at the University of Hong Kong and King’s College, London. Shuang’s research explores lives of Chinese mothers in colonial Hong Kong and the United Kingdom after the Second World …

30/09/18

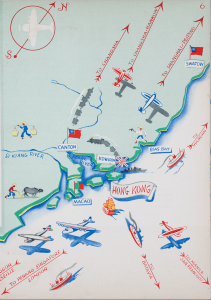

“All Roads Lead to Hong Kong”: People, City, Empires

Hong Kong History Project Conference

6-7 June 2019, University of Hong Kong

Keynote speaker: Henry Yu, Associate Professor, Department of History, University of British Columbia

28/09/18

Our guest writer this week is Luca Yau, who’s set to start her PhD at Trinity College Dublin in March 2019. During her MPhil study at Lingnan University, Luca explored the representations and self-representations of Hakka women since the …

17/09/18Our guest writer this week is Shuang Wu, PhD student at the University of Hong Kong and King’s College, London. Shuang’s research explores lives of Chinese mothers in colonial Hong Kong and the United Kingdom after the Second World …

30/09/18

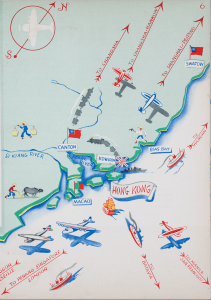

“All Roads Lead to Hong Kong”: People, City, Empires

Hong Kong History Project Conference

6-7 June 2019, University of Hong Kong

Keynote speaker: Henry Yu, Associate Professor, Department of History, University of British Columbia

28/09/18Our guest writer this week is Luca Yau, who’s set to start her PhD at Trinity College Dublin in March 2019. During her MPhil study at Lingnan University, Luca explored the representations and self-representations of Hakka women since the …

17/09/18