Showing 11-20 of 25 items

Where There's a Will There's a Way: Finding My Ancestors in China and Hong Kong by Natalie Fong 鄺黎頌 My research journey started in London, where I completed an MA in Victorian Studies at Birkbeck College, University of London, in 2006. For one assignment, I analysed representations of nineteenth-century Chinese opium dens in London's East End in literary texts and contemporary accounts. Living in London again in 2013, I researched

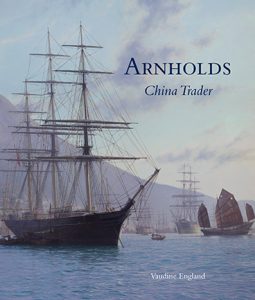

BY VAUDINE ENGLAND At first glance, a history of a company best known for selling building products, especially sanitary ware, might seem a little dull. This was not a big name like Jardines or Swires; not even Dodwells or Gibb Livingston. This was Arnhold & Company. Looking back at the nineteenth century you won’t even find such a firm, but you will find Arnhold, Karberg & Co, and indeed, they

This week we have Dr. Edward Vickers of Kyushu University reflecting on the History of Education in Hong Kong. The History of Education in Hong Kong - a bibliographical note by Edward Vickers The politics of education in Hong Kong has attracted headlines in recent years, especially since the 2012 controversy over plans to introduce a new Moral and National Education school subject. The resulting furore launched the political careers

The Project has recently established a facebook group which serves as an academic network for all ECRs/PGRs working on Hong Kong History. We hope the group would allow members to connect with others in the field, and share with each other news on hk-related events, funding opportunities, training and jobs. Join our group if you're also young scholars working in the field!

By Vaudine England If talking about race has been hard, how much harder has it been to accept that racism in statecraft has never been the sole preserve of white people. Not only Western imperialists have been racist; the Chinese were, and are, too. Proof of this is found, if any were needed, in the work of Frank Dikotter, back when he was still at SOAS. His analysis of ideas

By Vaudine England The thought behind a lot of these ruminations in this blog is that the subject of race in empire, specifically with relation to Hong Kong, has been grossly under-covered to date. Some Dutch academic friends wonder if it is the Britishness of Hong Kong studies — how else to explain, one wondered, the contrast between the huge swathes of scholarship done by the Dutch on ‘their Eurasians’

There are a fair few files relating to the history of Hong Kong among the large collection of Foreign and Colonial Office archival material still retained by the department, largely held at Hanslope Park. This 'secret archive' was finally acknowledged in 2011 following a ruling by High Court judge as part of a suit brought by five Mau Mau members over torture and mutilation during the Kenya 'Emergency' in the 1950s. Following

By Vaudine England Since the death of Dan Waters, aged 95, in Hong Kong on 27 January this year, he has rightly been lauded for many things: charm and personality, astounding memory, karate black belt, marathons after 60, and of course being such an inspiration to anyone interested in Hong Kong’s earlier days. His own life was impressive, from being a ‘desert rat’ under Montgomery in World War Two to

By Vaudine England Lethbridge’s article, 'The Yellow Fever', had concluded with an image of how the different, mostly non-Chinese peoples of Hong Kong interacted, or not: ‘The full flavour of the European community is to be savoured at a gala occasion… at the City Hall. Then the various layers, tier upon tier, are exhibited in the foyer: befurred and bejewelled Continentals, leading matriarchs, gilded youths and bright young girls back

Dissertation Reviews has posted a review of Kaori Abe's fascinating doctoral dissertation, The City of Intermediaries: Compradors in Hong Kong from the 1830s to the 1880s. Take a look at: http://dissertationreviews.org/archives/12498. Kaori is currently Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Nanyang Technological University. She completed her PhD in the Department of History at the University of Bristol under the supervision of Prof. Robert Bickers. Also