One of the Centre’s mission is to nurture a new generation of Hong Kong historians.

A Early Career Scholar Network was created under the Hong Kong History Centre in June 2023. It intends to help create a community of Hong Kong historians and offer a platform for face-to-face interaction and academic exchange among young scholars. Research students and fresh doctoral graduates working on socioeconomic, political and cultural history of Hong Kong and its global relevance are welcomed. We usually meet thrice a year (February, June and October) with participants taking turn to present their works in each meeting. Financial support is provided for attending these sessions.

Please write to Prof. Ray Yep, Research Director of Hong Kong History Centre, at rekmy@bristol.ac.uk, if you are interested in joining this Network.

——

In this post, we would like to introduce Nathanael Lai, a member of the Network.

Nathanael Lai is a PhD student in University of Cambridge. In the note written by him below, he shares with us his reflections on his academic journey and current project on popular politics and Hong Kong’s regional connections.

****

I was – I still am – struck by what I first read in December 2020. I was two months into graduate studies, starting to feel inundated by the sea of materials I must consume daily. But I could not put down Tim Harper’s then freshly published magnum opus. Underground Asia traces a connected arc of anti-colonial struggles across early-twentieth-century Asia. Hong Kong was a key site of connections, as revolutionaries banded together, sharing resources and drawing strength from a “sense of co-presence.” The book ends with Hong Kong. There, in a cell, Indonesian anti-colonialist Tan Malaka once said, hauntingly, to his British interrogators: “Remember this. My voice will be louder from the grave than ever it was while I walked the earth.”

My research to date embraces two themes of the book: popular politics and Hong Kong’s regional connections. My undergraduate thesis at HKU centred around the so-called 1956 riots in Hong Kong, a spillover from disputes in today’s Li Cheng Uk Estate on 10 October, the national day of the Republic of China. I was engrossed in the way the disturbances were narrated – not just by the state but by governor Alexander Grantham himself. His official report on the incident, published in English and Chinese, holds a special place in my intellectual journey. It introduced me to questions surrounding colonial statecraft, mass resistance, and the politics of translation. It opened up for me the world of historical research.

October 1956 was no less turbulent for Singapore. Clashes ensued from student protests in Chinese middle schools. I forayed into tracing Hong Kong’s Southeast Asian connections in my MPhil research at Cambridge. It was an experiment in writing “entangled histories” of Hong Kong and Singapore at a time when disturbances swept almost simultaneously across both colonies. British officials learnt from one another in quelling upheavals, while itinerant triads and intellectuals, “yellow culture,” and human rights discourses underpinned these episodes of dissent. Hong Kong’s history – I tasted and did for the first time – stretches well beyond Hong Kong.

The politics of the Cold War coursed through Hong Kong and Southeast Asia. My previous research crystallised into my PhD study. It scrutinises how historical actors articulated politics beyond “binaries” of the Cold War era: pro-communist versus anti-communist, left versus right, pro-Beijing versus pro-Taipei. I am invested in the Chinese capitalists, educationalists, journalists, and athletes travelling across 1950s Hong Kong and Southeast Asia – along what was effectively a Hong Kong-Singapore-Thailand corridor. Hong Kong’s history is part of Southeast Asia’s and vice versa. Indeed, my project afforded me the fortune of travelling, like my subjects, to different places, collecting pieces of Hong Kong’s past in far-flung archives and libraries: Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Taipei.

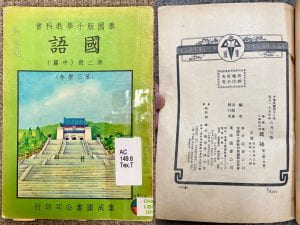

Hong Kong was at the heart of Bangkok. The colony figured in the 1950s and 60s as a de facto “centre of cultural China” for Thailand’s Chinese communities. From newspapers to Teochew-dialect operas, from films to wuxia (martial arts) novels, Hong Kong’s cultural productions filled Bangkok’s Chinatown and beyond. Part of my research has delved into Chinese-language textbooks used in Thailand’s Chinese schools. Designed with a view to promoting the Kuomintang, they were edited by educationalists from across Hong Kong, Bangkok, and Taiwan, and published in Hong Kong.

Chinese-language textbooks published in Hong Kong and used in Thailand (Source: Chinese in Southeast Asia Collection, Central Library, National University of Singapore)

香港出版之泰國中文教科書 (資料來源:新加坡國立大學圖書館東南亞華人特藏)

Hong Kong was at the heart of Southeast Asia. Another part of my research centres on Sing Tao Daily. This well-known Hong Kong newspaper was once the cornerstone of a media empire spanning Hong Kong and Southeast Asia: tycoon Aw Boon Haw’s “Star” newspapers. One journalist by the name of Jimmy Wu – branded by many as “leftist,” whose life I am still trailing in earnest – started off as Sing Tao’s chief reporter. But he later became the women’s column editor of Singapore’s Sin Chew Jit Poh and then chief editor of Bangkok’s Sing Sian Yer Pao. He drew on his Hong Kong contacts as he moved through this constellation of “Star” newspapers. He pieced together ideas about gender and politics at the same time as he revealed his own in Southeast Asia.

Hong Kong is at the heart of the world. My research has taught me Hong Kong’s role in the making of Southeast Asia. But the city was and is embedded in the region and beyond. I don’t take for granted the privilege to research the history of Hong Kong alongside other historians committed to the city’s regional and global connections. Nor do I take as given the chance here to contribute, however slightly, to the University of Bristol’s Hong Kong History Centre, one of the institutes flourishing outside Hong Kong that is dedicated to the city’s past. Hong Kong history promises to be part and parcel of the world, and I am grateful there is one part I could play in this.

****

我曾經 —— 現在仍然 —— 被幾年前第一次讀到的一本著作所震撼。當時我開始攻讀碩士兩個月,對每天需要閲讀海量的學術著作開始感到不知所措。但對於Tim Harper當時出版不久的一本鉅作,我卻毫不厭倦。《地下亞洲(Underground Asia)》追溯二十世紀初亞洲各地反殖民鬥爭的互聯關係。香港是革命家聚集、共享情報,並從彼此資取力量的一個重要樞紐。該著作以香港作結。印尼反殖民主義者Tan Malaka曾在當地的一個牢房裡,對審問他的英國官員說:「記住,我在墳墓裡的呼聲,將比我在世時的更為響亮。」

我目前為止的研究涵蓋書中兩大主題:「大眾政治」(popular politics)和香港的區域性聯繫。我在港大的學士論文追溯1956年10 月 10 日(中華民國國慶日)在香港發生、由李鄭屋村居民糾紛引發的一場騷亂(所謂五六或雙十暴動)。我對英國殖民政府 —— 尤其是港督葛量洪(Alexander Grantham)本人 —— 如何敘述當時的情況非常感興趣。葛量洪就事件所撰寫,並以中英文出版的官方報告,對我的學術旅程具有特別意義。這份報告讓我更加了解殖民統治手法、群眾抵抗,以至翻譯的政治等議題。更重要的是,它帶我走進歷史研究的世界。

1956 年 10 月對新加坡來說同樣動盪不安。當地華校學生的示威行動觸發了大規模警民衝突。在英國劍橋攻讀碩士期間,我開始探索香港與東南亞的連結。我以當時在香港和新加坡幾乎同時發生的騷動為中心,嘗試剖析兩地歷史如何「交織」(entangle)起來。我發現當時兩地英國官員就如何平息動亂互相學習。同時,遊走香港以及東南亞的黑社會和知識分子、猖獗的「黃色文化」,以及有關人權之思潮貫穿港星兩地的反抗事件。我第一次意識到香港歷史原來遠遠超出香港的地域界限。

National Archives of Thailand (left); National Archives of Singapore (right)

泰國國家檔案庫 (左); 新加坡國家檔案庫(右)

冷戰政治席捲香港和東南亞。過往的研究塑造了我的博士論文題目。我的研究審視歷史人物如何表達冷戰時期不同「二元框架」(binaries)以外的政治思維,嘗試進一步打破當年不同所謂對立的意識形態:親共與反共、左派與右派、親中與親台。我特別關注在五十年代穿梭香港、新加坡和泰國三地(可謂「港星泰」走廊)的華人資本家、教育家、記者以及運動員,他們如何遊走冷戰時代的政治版圖。我認為,香港史是東南亞史的一部分,反之亦然。我的研究正正讓我有幸可以跟我關注的歷史人物一樣,遊走曼谷、清邁、吉隆坡、新加坡、台北等地,在不同檔案庫與圖書館收集與香港歷史相關的珍貴資料。

香港曾在曼谷扮演關鍵角色。上世紀五六十年代,香港對泰國華人社群而言是「中國文化」的源頭。香港的文化出品 —— 無論是報紙、潮州戲劇、電影或武俠小說 —— 均遍佈曼谷唐人街及其他社區。我的研究其中一部分正正探討泰國華校當年使用的中文教科書。部分教材以宣傳國民黨為目標,由香港、曼谷及台灣的教育家編輯,在香港出版。

香港曾在東南亞扮演關鍵角色。我的研究另一部分聚焦港人熟悉的《星島日報》。該報曾經是大亨胡文虎橫跨香港及東南亞的報紙帝國 —— 「星系報業」 —— 之重要基石。我現時仍在努力追蹤一位當年被標籤為「左派」的記者吳占美。四十至五十年代初,他是《星島》的採訪主任;一九五八年,他到新加坡擔任《星洲日報》的婦女版主編,及後成為曼谷《星暹日報》主編。吳氏在穿梭各「星系」報紙的同時,不忘善用他在香港建立的人脈;在東南亞編織有關性別等議題的報導同時,亦表露了自己的觀點與政治。

Southeast Asian Chinese Language Press Seminar in Hong Kong, 1966. Sally Aw (Sing Tao’s proprietor) as organiser (first row fifth from the left); Jimmy Wu (Bangkok Sing Sian Yer Pao’s chief editor) as participant (second row first from the right). (Source: Chinese Overseas Collection, University Library, Chinese University of Hong Kong)

1966年於香港舉辦的東南亞中文報紙研討會。胡仙(《星島日報》持有人)為主辦人之一(前排左起第五位);吳占美(曼谷《星暹日報》主編)則為參加者之一(中排右起第一位)。(資料來源:香港中文大學圖書館海外華人特藏)

香港在世界扮演關鍵角色。我的研究使我了解到香港在東南亞發展史中的地位。但香港的影響,不論以前抑或現在,均超越其自身以至東南亞這區域。我慶幸能夠與其他歷史學家共同研究香港歷史與其他區域以至世界的聯繫。我亦高興能夠在此 —— 英國布里斯托大學香港史研究中心(現時香港以外其中一所發展旺盛、聚焦香港史的研究中心)—— 分享自己的研究和願景。我深信香港史會成為世界重要的一部分,而我為自己可以為此出一分力感到榮幸。