One of the Centre’s mission is to nurture a new generation of Hong Kong historians.

A Early Career Scholar Network was created under the Hong Kong History Centre in June 2023. It intends to help create a community of Hong Kong historians and offer a platform for face-to-face interaction and academic exchange among young scholars. Research students and fresh doctoral graduates working on socioeconomic, political and cultural history of Hong Kong and its global relevance are welcomed. We usually meet thrice a year (February, June and October) with participants taking turn to present their works in each meeting. Financial support is provided for attending these sessions.

Please write to Prof. Ray Yep, Research Director of Hong Kong History Centre, at rekmy@bristol.ac.uk, if you are interested in joining this Network.

——

In this post, we would like to introduce Alex Cheung, a member of the Network.

Alex Cheung is a PhD student in Bristol. In the note written by him below, he shares with us his reflections on his academic journey and current project on experience of migration.

****

It is not easy to trace the exact moment I developed an interest in history, but I still remember the younger me always getting fascinated by history stories on TV, in books and video games. When I was studying history at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, I was first introduced to the field of Hong Kong history. I also realised history is not just about remarkable events; it is closely relevant to ordinary life. Back then, I was particularly interested in urban history and planning history – whereas Hong Kong is described as a laissez faire city, the government and merchants had always been shaping the landscape of the city. During my MPhil study, I wrote a thesis ‘Town Planning of New Kowloon and Colonial Governance in Hong Kong, 1898-1941’ and explored how the colonial government planned and developed part of the New Territories (the government named it as ‘New Kowloon’) after the lease of the New Territories in 1898. I argued that the Hong Kong government did not simply copy the model of urban planning from Britain and other colonies. It negotiated with property developers over issues including public health, property speculation and terms of New Territories leases. Through this process, it introduced into the colony various practices of urban planning.

It is not easy to trace the exact moment I developed an interest in history, but I still remember the younger me always getting fascinated by history stories on TV, in books and video games. When I was studying history at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, I was first introduced to the field of Hong Kong history. I also realised history is not just about remarkable events; it is closely relevant to ordinary life. Back then, I was particularly interested in urban history and planning history – whereas Hong Kong is described as a laissez faire city, the government and merchants had always been shaping the landscape of the city. During my MPhil study, I wrote a thesis ‘Town Planning of New Kowloon and Colonial Governance in Hong Kong, 1898-1941’ and explored how the colonial government planned and developed part of the New Territories (the government named it as ‘New Kowloon’) after the lease of the New Territories in 1898. I argued that the Hong Kong government did not simply copy the model of urban planning from Britain and other colonies. It negotiated with property developers over issues including public health, property speculation and terms of New Territories leases. Through this process, it introduced into the colony various practices of urban planning.

Having completed my MPhil thesis, I started rethinking whether the people merely passively lived in urban space as designated by the government and merchants. I developed greater interest in understanding the lived experience of urban dwellers and individual agency in history. When I drafted my PhD research proposal, I once conceived of studying the daily life of Chinese tenement dwellers in the early twentieth century. However, I gradually noticed the mobility of lower-class population of Hong Kong – they came from different places to Hong Kong and they stayed or left for different reasons. Living in Hong Kong was only part of their life. As I sought to explain the relationship between urban life in Hong Kong and experience of migration, I formulated my current research project, which is tentatively titled as ‘Seeking Home in the Colonial Port: Migration and Settlement of Chinese Workers in Hong Kong, c. 1900-1941’. In this research, I examine everyday experience of the working classes in dwelling and working in the port city and moving across borders. I also analyse how the colonial government and public discussed and dealt with associated problems. Apart from notions like race and class divisions, perceived differences between local residents and outsiders also complicated these discussions. Encountering these discursive and practical differentiations, lower-class migrants lived in an unsettled condition and resorted to migration as their tactic.

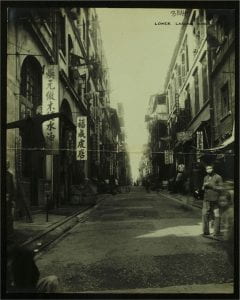

In search of the experiences of lower-class migrants and attitudes of the government and local society towards them, I will examine a variety of sources. Apart from understanding officials’ perception and decision-making process through the colonial archive, I will also utilise newspapers and magazines to reconstruct how ordinary life was like. I will particularly pay attention to reports on police and court cases. In these cases, ordinary people were arrested and prosecuted for all sorts of crimes and offences. At the same time, they also left written records of their ideas and actions through interrogations of the police and the court (despite these records were usually written from the perspective of the interrogators). Apart from textual sources, I will also study the urban environment and details of life in old photos.

Highlighting labour mobility can help us understand the complicated relationship of the working class and Hong Kong. Like port cities all over the world, Hong Kong emerged amidst the growth of global trade. People from different places came to seek fortunes, rendering the boundary between locals and outsiders constantly in flux. We usually stereotyped the workers in Hong Kong before the Second World War as passer-by. They saw mainland China as home (or to be more precise, saw villages in southern China as home), temporarily stayed in Hong Kong for work and would return to their native villages for retirement and death. Such a narrative emphasised that they were bound to return to their home villages and downplayed how their experiences in Hong Kong affected their decisions of leaving or staying. Enduring inequalities in the colonial power relations, people living in Hong Kong once adopted different tactics to struggle for existence.

Returning to the present, many Hongkongers are migrating overseas and moving between different places more frequently. Despite the historical context varies through time, the mobility of Hong Kong residents is common in past and present. I hope my research can facilitate understanding of the experience of migration and stimulate thinking about opportunities and restraints inherent in it.

Chinese tenements, the typical type of accommodation for working-class population in colonial Hong Kong (photo from the National Archives, London, CO 129/450, p. 381H (16th December 1918).

****

回溯甚麼時候開始對歷史產生興趣並不容易,但還記得小時的我總對電視、書本、電子遊戲等各種媒介接觸到的歷史故事着迷不已。直至我在香港中文大學修讀歷史本科時,開始接觸到香港史,同時認識到歷史不只是各種重大的事件,更是與大眾的日常生活切身相關。當時我對城市史、城市規劃史尤其感興趣——香港常被形容為一個自由放任(laissez faire)的城市,但政府、商人卻一直在形塑這個城市的景觀。為此,我在碩士時期撰寫了論文〈新九龍城市規劃與香港殖民管治,1898-1941年〉,探討殖民政府租借新界後,將其中一部份(政府將之命名為「新九龍」)規劃和開發為市區的過程。香港政府並非直接套用英國及其地殖民地的城市規劃模式,而是就本地的公共衛生、房地產投機、新界地契條款等問題與地產商協商,在這過程中引入各種城市規劃的實踐。

完成了碩士論文後,我開始反思,大眾只是被動地按照政府、商人設定的方式在城市空間中生活嗎?我更加希望了解城市居民的生活經驗、個體在歷史中的角色。我在草擬博士研究計劃初時,曾構想研究二十世紀初唐樓住客的生活史,但逐漸注意到當時香港底層居民的流動性——他們從不同地方前來香港謀生,又因各種原因而留下或離去,在香港居住只佔他們生命的一部份。我希望闡明香港的城市生活與移民經驗的關係,因此逐漸訂定目前的研究計劃,暫名為〈在殖民地港口尋覓家園:香港華工的遷移與定居,約1900-1941年〉。在這研究中,我會關注勞工階層移民在港口城市居住、工作、跨境遷移等日常生活的經驗,以及殖民政府及公眾如何討論或處理相關的問題。除了種族、階級之分以外,分別本地人與暫居者的觀念,都使這些討論更形複雜;面對這些話語和實踐上的區分,底層移民處於一種無法安頓下來的狀態,亦以遷移為他們的生存策略。

為了追尋底層移民的經歷、政府和本地社會如何看待他們,我會考察多種不同的資料。除了透過殖民地檔案了解官員的想法和決策過程、政府和平民的互動之外,我亦會運用報紙雜誌重構普通人的生活,其中特別留意各種案件的報導。在這些案件中,普通人因犯大小罪行而被捕、檢控,同時亦在警察或法庭的審訊下留下了有關他們的思想、行動的文字記錄(儘管這些記錄多以審訊者的觀點記載)。文字記載以外,我亦會考察舊照片中的城市環境及生活細節。

關注工人的流動性有助我們理解工人階層與香港這座城市的複雜關係。像世界各地的港口城市,香港因全球貿易增長而崛起,吸引不同地方的人前來尋找機會,使本地人與外來人的界線持續變動。對於二次世界大戰前來到香港的工人,我們一般認為他們只是過客,以中國大陸為家(更準確地說,以華南地區的農村為家),在香港暫居和工作後便回鄉老死。這樣的說法強調他們必然會回到家鄉,忽略了在香港的際遇如何影響他們的去留、他們如何作出選擇。面對殖民地的權力關係造成的種種不平等,在香港生活的人曾採取的不同策略掙扎求存。

回到當下,不少香港人移居外地,更頻繁地往返不同地方。具體的歷史脈絡不盡相同,但香港居民的流動性卻是古今相通的。我希望我的研究能促進理解不同歷史時空移民的經驗,思考其中面對的機會和限制。